Spoilers below

Copyright of MGM

One of my all-time favorite horror films is Mad Love from 1935, directed by Karl Freund and produced by Columbia Pictures. Based on French author Maurice Lenard’s novel The Hands of Orlac, it’s one of the first great examples of body horror in movies. Lenard’s book had previously been adapted 11 years earlier in The Hands of Orlac starring Conrad Veidt, which I’ve never seen.

The cast includes (bald!) Peter Lorre, Colin Clive, and Frances Drake, with Ted Healy, Keye Luke, Edward Brophy, Sara Haden, and Billy Gilbert in supporting roles. Set in Paris, Lorre plays Dr. Gogol, a brilliant scientist who falls in love with actress Yvonne Orlac (Drake). Yvonne’s husband, famed concert pianist Stephen Orlac, has his hands destroyed in a train crash. Dr. Gogol, in an attempt to get with Yvonne, amputates Orlac’s hands and replaces them with the hands of an executed knife-thrower. Orlac soon realizes his hands can’t play the piano well, but they sure can throw knives. The plot may sound a bit contrived and silly, but it works thanks to Freund’s direction and superb acting by Lorre.

Mad Love was Karl Freund’s last project as a director, and visually speaking, he was one of the best of the early sound era. Freund was one of many German émigrés who came over to show us Americans how filmmaking and cinematography is really done. I say that because there had been tons of innovative techniques during the silent era, but those quickly became lost with the advent of sound. A lot of early talkies from 1929, 1930, and 1931 have a very stagey feel with stiff camerawork, but Freund and a lot of his fellow Germans continued using dynamic techniques to make movies more visually interesting.

Freund started out his career (and ended it) as a cinematographer in Germany where he pioneered unchained camera technique. This let the camera move rather than remaining stationary, allowing filmmakers to use tracking shots, pans, tilts, and crane shots. It may seem rudimentary today, and that’s because it is; every filmmaker has been using them for nearly 100 years thanks to Freund. Also keep in mind that cameras are a bit lighter weight today than they used to be. Back in the 1920s, they were massive, so dynamic camerawork wasn’t as easy.

After emigrating to the U.S., Freund did the cinematography for a few horror films like Dracula and Murders In The Rue Morgue, both starring Bela Lugosi. Freund had worked as a cinematographer for 16 years before he directed his first horror film, The Mummy (he’d previously directed a film in Germany in the 1920s) and directed 6 more films before making Mad Love, including The Mummy with Boris Karloff and Zita Johann.

Karl Freund directing Zita Johann on The Mummy (1932)

He spent the next twenty years manufacturing cameras before he was convinced by Desi Arnaz to be the cinematographer for I Love Lucy, where he once again helped pioneer a new camera and lighting technique that is still used on sitcoms today. Freund designed “flat lighting,” which placed fixed lights above the set, underneath the cameras, and below the floor. This eliminated shadows, meaning cameras could be moved around for continuous shooting. Three cameras are on the set: one in the middle for wide shots and two on either side of the stage for close-ups. All of this allowed actors to move around the set without having to reshoot, allowing all the jokes to remain fresh for the live studio audience. While almost every television show was broadcast live back then (including other sitcoms like The Honeymooners), Lucy was one of the few that was recorded beforehand. Freund wasn’t the first to invent multiple camera setup for television, but he and Desilu Productions (Lucy and Desi’s TV company) pioneered it by filming in front of a live audience and using 35mm film.

I spent so much time on Freund to illustrate how great the cinematography is in this film. I also think it’s important to realize how dynamic Freund was as a cinematographer and director, to go from shooting some of the most famous Expressionist and Horror films ever made—which are drenched in dark shadows and high-contrast lighting—to flat lighting for sitcoms.

Cinematography credit goes to Greg Toland, who innovated deep focus cinematography. He’s most famous for shooting Citizen Kane and The Best Years of Our Lives.

All of this is to say that Mad Love has some great shots and Freund's Expressionist beginnings can be felt in the film.

The film stars the miraculous, leering, wide-eyed Peter Lorre in one of his best performances and most iconic looks.

Mad Love was Lorre’s American film debut after having completed several films in England, including Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much. Lorre signed a contract with Columbia Pictures and desperately wanted to make a film adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s Crime And Punishment. Harry Cohn, the infamous head of Columbia, agreed to finance the picture so long as Lorre be loaned out to MGM to make a horror film. Lorre reluctantly agreed and was signed on for Mad Love. He apparently didn’t enjoy making the film, but he could’ve fooled me as he seems to be having the time of his life in the film and the trailer. The trailer for this is great, mainly because we get to see Peter Lorre relaxing at home (in a suit, no less) with a dog that’s as big as he is.

Peter Lorre in the film's trailer

Lorre is spellbindingly creepy as Dr. Gogol. It’s one of his best performances as we see him go insane with love and jealousy.

From his very first scene, we know something isn’t right with Dr. Gogol. It takes place at Le Théatre des Horreurs (based on the Grand Guignol) where the doctor goes to see the same horror play every single night. But this particular night is the final performance for the show’s star, Yvonne Orlac (Frances Drake), who Gogol is obsessed with.

After walking into the lobby, he stares longingly at a wax statue of Yvonne with a slight, almost euphoric smile on his face until he’s interrupted by a drunk patron. “Don’t be jealous my friend,” the patron tells Gogol, “She’s not for either of us. She’s only wax!” Though it’s apparent she’s far more than that to Gogol.

During the horror play, we see Gogol sitting in his box. As Yvonne is tortured on the stage, there’s a closeup of Lorre blinking in a rather disturbing manner. Clearly Gogol is getting some type of psychosexual thrill out of seeing Yvonne being tortured. Pretty racy for the 1930s, but Lorre’s expression makes the subtext perfectly clear.

The next scene has Gogol visit Yvonne’s dressing room after the show. Gogol explains how he’s watched her show every night, and Lorre’s delivery is perfectly creepy. “Every night I’ve watched you and tonight, the last night, I felt I must come and thank you for—for what you’ve meant to me . . . And when the theatre reopens, I shall be in my box again every night.”

Yvonne explains it’s her last show and she’s moving to England with her husband, the concert pianist Stephen Orlac (Colin Clive).

Lorre responds confused. “Your . . . husband?” It’s clear the doctor isn’t taking it well internally. He tells her, “You know, I’ve come to depend on seeing you every night. I must see you again. I must!”

Luckily Yvonne is saved by being carried off by the cast to a party where Dr. Gogol forcibly kisses her. She’s rightfully horrified.

After the party ends, Dr. Gogol pays a man to deliver the statue of Yvonne to his house the next morning.

I know this is heavy on plot, but all of this happens in the opening 10-15 minutes of the film. What’s great about Lorre is he portrays Gogol as a guy who clearly has a few screws loose while also being very genuine and, dare I say, innocent. Innocent may be the wrong word, but there’s an authentic vulnerability to his character that we as the audience can’t help but feel sorry for the guy.

What makes Lorre’s performance so memorable is we see his Dr. Gogol performing acts of kindness. He runs a clinic where he operates on those in need. A few scenes later, he and his surgical colleague Dr Wong (Keye Luke) are caring for a little girl who they’ll operate on later.

“Her first natural sleep in weeks.” Says Dr. Wong.

“Poor little thing.” Replies Gogol.

And he means it. There is genuine sadness in Lorre’s voice as utters the line. About halfway through the movie after operating on the girl, the girl’s mother tries to pay Gogol for the operation.

“I’ve saved it,” She says, “50 Francs. All I have in the world.”

Dr. Gogol refuses it. “I do not operate for money.”

These kind-hearted acts allow us to sympathize with Gogol. He seems to be a good man at heart, but we’re reminded again and again that he isn’t all there. He’s asked to attend an execution the next day, which he seems oddly excited about. The man on the literal chopping block—he’s executed by guillotine—is Rollo the American knife-thrower, wonderfully played by Edward Brophy (more on him later).

A few scenes later, Dr. Gogol is informed that Yvonne’s husband, the concert pianist Stephen Orlac, has been in a train accident that crushed his hands. Even though Yvonne can’t stand Dr. Gogol, she realizes he’s the only person who may be able to save her husband’s hands without amputating them. The scene between Yvonne and Gogol is another great acting vehicle for Lorre. He sincerely wants to help her husband, but also hopes that doing so will make Yvonne warm up to him. Lorre’s voice is genuine and filled with disappointment as he explains there’s no way to save her husband’s hands.

But right before surgery, Gogol gets an idea. He orders the body of Rollo to be delivered to his clinic and transplant’s the dead knife-thrower’s hands onto Orlac’s body.

All goes well for Orlac at first, but he quickly realizes he can’t play the piano. Oh, and his hands gravitate towards knives and other sharp objects. During an argument with his father, he angrily hurls a knife, only for it to stick straight up on a table. He goes to Gogol in a frenzied state, screaming “What have you done to me?” He demonstrates his hands’ ability to Gogol by throwing scalpels into the wall. The stick straight out just like knives. Lorre makes some great facial expressions during this scene; we can see the wheels turning in his head as he realizes Orlac’s horror can be used as an advantage. Dr. Gogol will try to drive Orlac insane so he can be with Yvonne.

Gogol spends the rest of film gaslighting Orlac. This culminates in the pianist’s father being found murdered with a knife in his back. The evidence points to Orlac, who witnesses saw fought with his father the day before and throwing a knife at him.

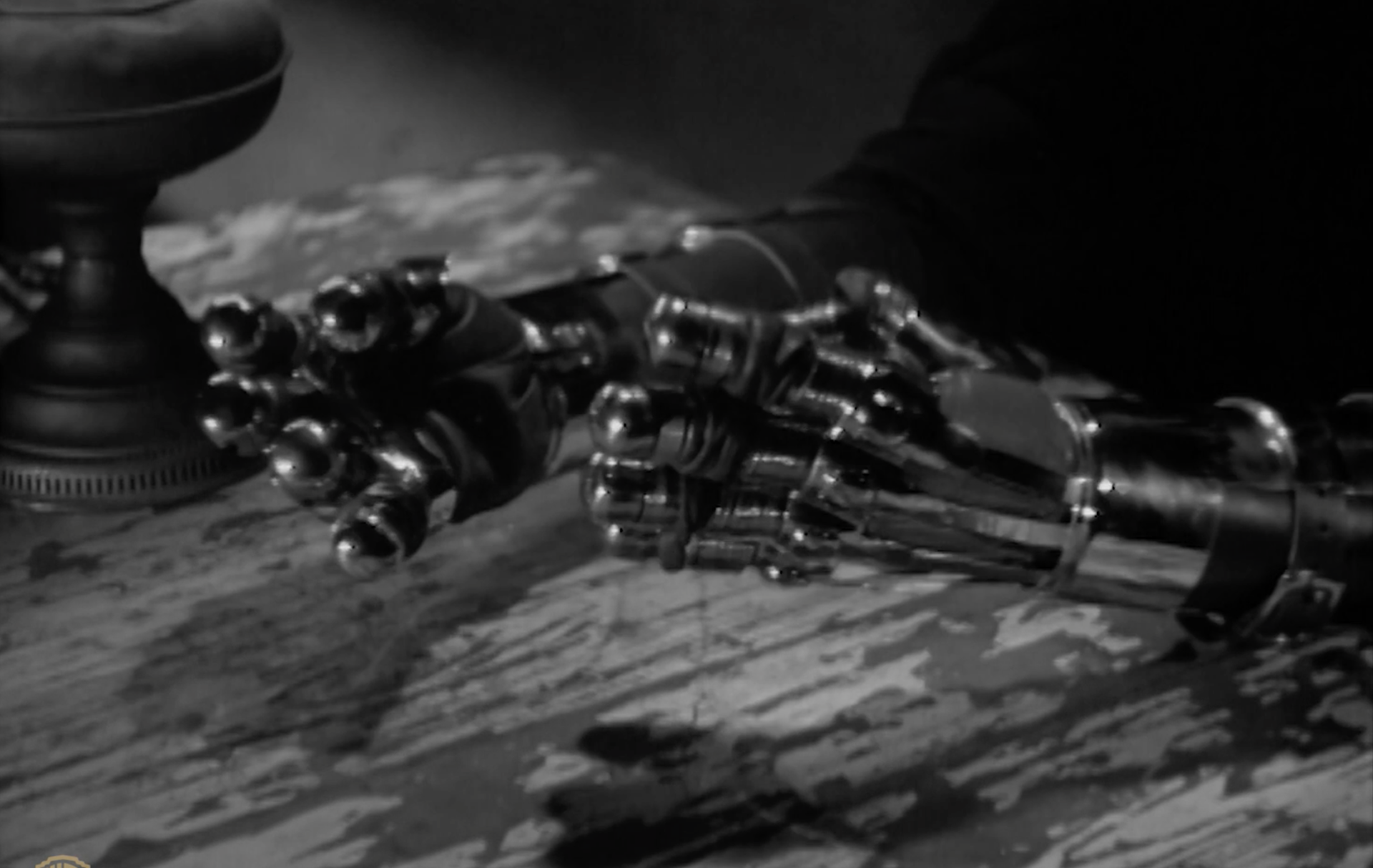

Later that night, Orlac visits a mysterious man in a dingy hotel. The man hides in the shadows at first—all we see are his metallic hands. His voice is quiet and raspy, never rising above a whisper. The man claims he’s Rollo the knife thrower (clearly Lorre) lets out a maniacal laugh.

This is probably the most well-known scene in the film and it’s not hard to see why: the dark lighting, Lorre’s silhouette, and his unforgettable costume with the goggles, neck brace, and metallic hands. It’s wonderful, atmospheric, and features marvelous acting on Lorre’s part.

Orlac is later arrested for murder. The next we see of Dr. Gogol is him drunkenly wandering back into his clinic as he celebrates Orlac’s arrest. By this point, Gogol has completely lost his mind, and Lorre is superb, giggling and howling in triumph.

After seeing Mad Love, Charlie Chaplin called Peter Lorre “the greatest living actor.” Deservedly high praise for one of Lorre’s many outstanding performances. Peter Lorre is one of a few legendary actors who was never nominated for an Academy Award. It’s a crime considering how beloved an actor he was and how passionate his performances were.

The other standout performance besides Lorre is Edward Brophy as Rollo the knife thrower. Edward Brophy was a character actor best remembered for voicing Timothy Q. Mouse in Dumbo, but he also appeared in movies like Freaks and The Thin Man. In Freaks he played one of the Rollo brothers, a knife-throwing act in the circus. It’s possible his character in Mad Love is either an homage to his portrayal in Freaks or the same character. Brophy’s performance stands out not because he plays Rollo as a demented killer, but as what may be the most stereotypical 1930s American ever.

Brophy’s performance as Rollo is very light-hearted and enthusiastic. When we first meet him, he’s on the same train as Stephen Orlac and is being transported to the guillotine. For a man sentenced to die, he takes it pretty well. Brophy has a very chipper, upbeat “gee, whiz!” attitude. When he sees the guillotine for the first time, he exclaims, “Boy! Ain’t that somethin’?” His final scene where he talks with Ted Healy before his execution is both heartfelt and humorous. “We all get it in the neck someday.”

Edward Brophy as Rollo the Knife Thrower and his reaction upon seeing the guillotine

As Brophy’s character indicates, there are nice bits of levity throughout the film. There’s the drunken patron who speaks to Yvonne’s wax statue in the beginning, a man being shushed for comforting his wife in Les Théatre des Horreurs, Billy Gilbert’s cameo as the autograph seeker, Ted Healy as the wise-cracking American reporter, and May Beatty as the drunken housekeeper Francoise.

It was a common trope at the time to have a drunk character as comic relief. Francois, Gogol’s maid, fits this role and May Beatty plays it rather well. It may seem a bit dated to us now, but I always enjoy her scenes.

I also want to mention Ted Healy. This is the only movie I’ve seen him in, but he’s best remembered for creating the Three Stooges. His mysterious death has also become a sort of Hollywood legend. His death was officially announced as a heart attack, some people believe he was involved in a fight outside the Café Trocadero that resulted in him being murdered. To this day no one knows exactly what happened, but it’s rumored that Academy Award-winning actor Wallace Beery and Albert Broccoli (who later produced the James Bond films) played a part in his death.

A final honorable mention to Keye Luke, who had a prolific acting career for almost 60 years and was a founding member of the Screen Actors Guild. I, like many, was introduced to him in Charlie Chan films where he played “Number One Son” Lee Chan but also saw him in The Good Earth (1937), the Green Hornet serial, and heard his voice on shows like Space Ghost and movies such as Enter The Dragon.

Ted Healy

Keye Luke

This film was both of its time and ahead of its time. Lots of horror and science fiction from this period revolved around some type of body horror. The concept of transplants became popular horror stories, and since it was a new idea, no one knew what the result might be. If you stitched someone’s head onto a different body, would the new head control the body or did the body still have autonomy of its own? If a brain transplant occurred, would the brain contain the personality of its original body? And if hands were grafted on to a new body, could they not have the old traits? Such was the basis for Maurice Lenard’s novel and this film. We know better now, of course, but I find the outdated science part of the film's charm.

The first successful hand transplant didn’t occur until 1998—63 years after Mad Love was released.