All images are copyrighted under Janus Films, Internacional Films Española, Alpine Productions, Peppercorn-Wormser Film Enterprises, and the Welles Estate.

“Chimes At Midnight” (released as “Falstaff" in the U.S.) has been my favorite Shakespeare film ever since I first saw it almost 6 years ago. Film critics consider it to be one of Orson Welles’s best films along with “Citizen Kane." Welles had a life-long fascination with Shakespeare and the character of Sir John Falstaff, who he touts as the hero of this film. “Chimes At Midnight” shows Welles not only as one of the best directors in film history, but also as one of the finest actors, casting directors, and editors that ever graced the silver screen. I say editor not only in relation to cutting film, but as an editor of texts. “Chimes At Midnight” is not an adaptation of one single Shakespearean play; instead, Welles created the script for this film by editing together most of “Henry IV Part 1,” sections of “Henry IV Part 2,” and a few scenes and lines of dialogue from “Richard II,” “Henry V,” and “The Merry Wives of Windsor.” This alone speaks to Welles’s amazing talent as an editor of texts: the fact that he’s able to smush 5 different plays into one film without ruining Shakespeare is an incredible feat. It’s downright awe-inspiring if you’ve read all those plays and then watch the film; the way Welles edits the texts together actually enhances Shakespeare’s lines and (in my opinion) makes them more accessible to general audiences than if they read all 5 plays back-to-back. The result is one of the finest Shakespearean films ever made: it’s perfectly shot, cast, acted, lit, and edited.

Most of the information I have comes from the Criterion Collection’s release, which contains a very informative commentary and interviews with Beatrice Welles, Simon Callow, Joseph McBride, and Keith Baxter (Prince Hal).

This is probably the best-cast Shakespearean film ever. Unlike other great Shakespeare films such as Kenneth Branagh’s “Hamlet,” everyone in “Chimes at Midnight” fits their part perfectly. I love Branagh’s “Hamlet,” but at times it feels like they cast some random celebrity who wandered onto the set. That’s not the case in Welles’s film.

Welles himself plays Falstaff and gives what is probably his greatest performance on film. His interpretation of Falstaff is that of a tragic figure, which is pretty unique since most people view him as a comedic figure. His Falstaff only acts clownish deliberately to save face, not because he's a clown at heart. He's funny because he wants to please Prince Hal. Welles said that Falstaff is a good man at his core. Falstaff does some lousy things, both in the plays and film, yet Welles makes it palatable and has us rooting for the old rogue. His performance is full of life and shows Falstaff as a man who loves indulgences, be it wine, food, women, or song. He’s loud and boisterous yet also very witty and sustained during the comedic scenes. During the melancholic scenes in the film’s second half, he’s more restrained and tired. Some of his best moments are when he’s sitting perfectly still and reacting to what is happening around him. It’s one of the few performances I’ve seen where the audience can see an actor thinking in character. His reactions and facial expressions during the coronation scene are heartbreaking and we can hear genuine emotion in his voice when he says, “I speak to thee, my heart!” Everyone praises Welles the filmmaker and director, but it’s not as common to praise his acting ability. His performance as Falstaff is his best. It’s easily one of the greatest performances in any Shakespeare film, and I think it ranks among the greatest performances ever captured on camera.

Falstaff also illustrates Welles's makeup skills. He's the only actor in the film who wears makeup, which is great as the rest of the cast's natural faces adds to the realistic atmosphere. Welles always wore makeup in his films, both as a means of transforming into his characters and to hide his own insecurities. He disliked his baby face and nose, almost always hiding them under heavy makeup and false noses in order to play characters older than himself. For "Chimes" he wore padding to accentuate Falstaff's girth, a fake nose, beard, and makeup to suggest advanced age. I think it's his best physical transformation next to Hank Quinlan in "Touch of Evil."

Orson Welles as Sir John Falstaff

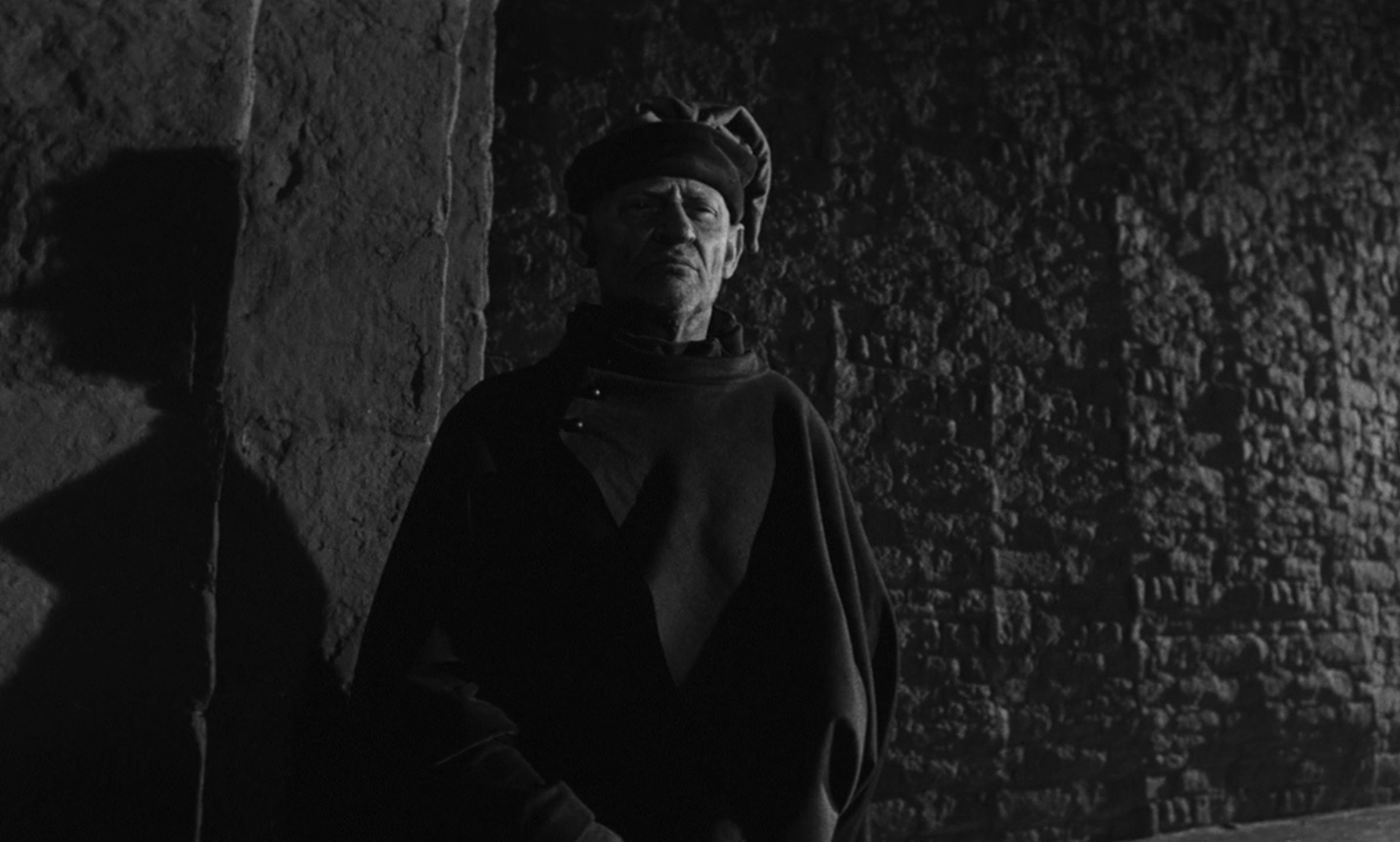

Sir John Gielgud, who in my opinion is the greatest male Shakespearean actor ever, plays Henry IV. I know a lot of people consider Laurence Olivier to be the best Shakespearean actor, but Gielgud is far more watchable in my opinion (I have a long list of British actors I’d rather watch than Olivier). As Henry IV, Gielgud is theatrical yet real: it’s clear he’s feeling the lines as he says them and the audience senses the vulnerability inside the man. I rarely get that with Olivier and most of the time I’m well aware I’m just watching an actor in a role. That’s not the case at all with Gielgud, especially in this film. His Henry IV is cold and icy; yet his guilt, vulnerability, and pain pierces through the screen. It also helps that Gielgud (along with Welles) had one of the greatest voices ever to be recorded—he practically sings the lines and makes Shakespeare’s text sound so beautiful.

Sir John Gielgud as King Henry IV

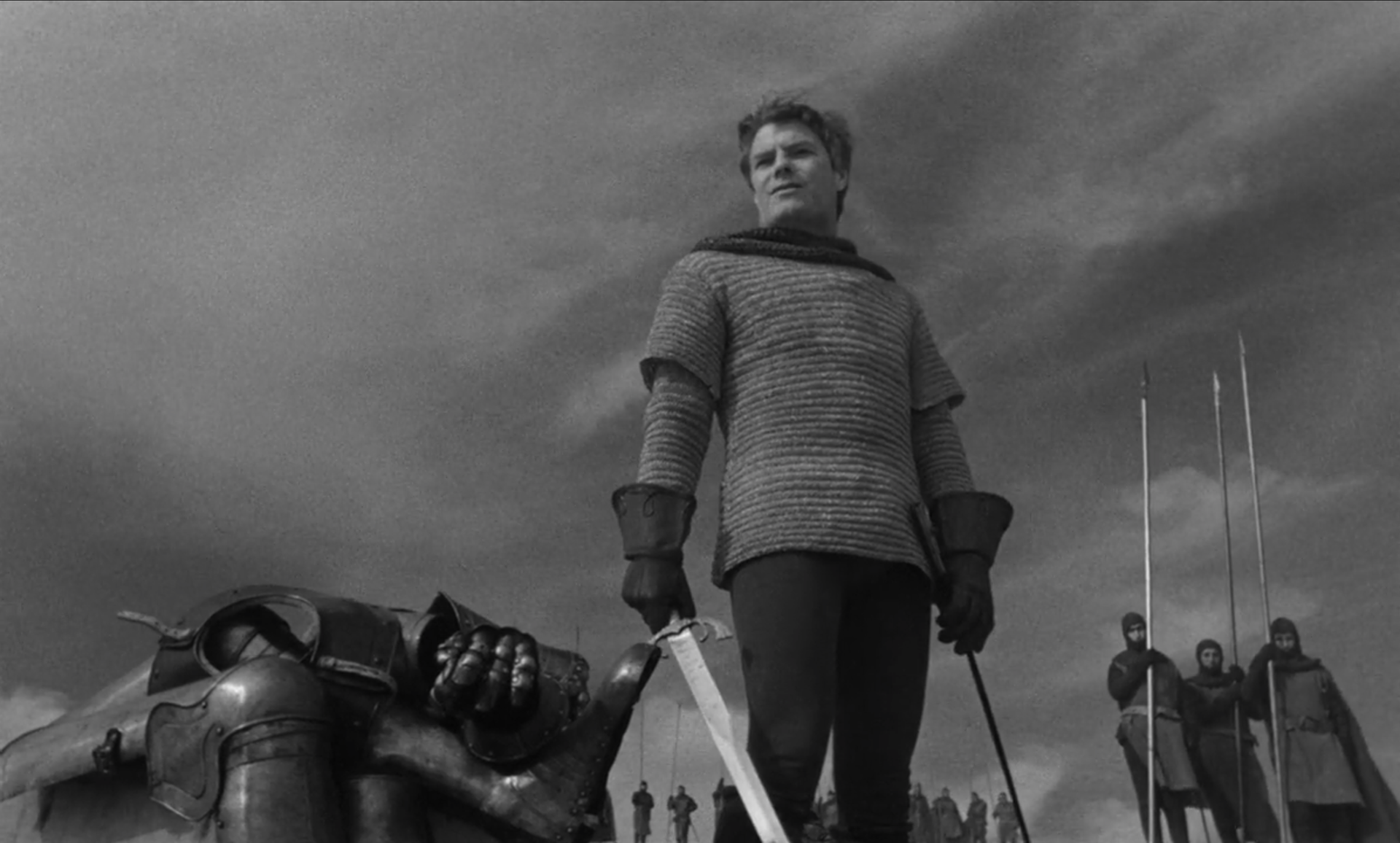

Keith Baxter, a relative newcomer to film, gives an amazing performance as Prince Hal/Henry V. He plays the prince with remarkable zest and life in his scenes with Falstaff, is dignified and solemn during the battle scenes, insecure and fearful around his father, and cold during his coronation. In other words, he acts differently depending on the circumstances he’s in. We truly get a sense that this is a young man who is trying to find his way in the world; he’s torn between wanting to live it up with Falstaff versus his desire to appease his father and prepare to inherit the crown. Baxter’s performance is a mix of vivaciousness, humor, revelry, dignity, seriousness, and solemnity. It’s an amazing performance for a newcomer to film and makes one wonder why Baxter never had a bigger movie career. Maybe he prefers stage to screen. If that’s the case, it’s our loss because he’s a tremendous actor.

Keith Baxter as Prince Hal

The rest of the cast is excellent in supporting roles. Dame Margaret Rutherford, one of the great English comedic and Classical actresses who was famous for starring in the Miss Marple films, gives a wonderful performance as Mistress Quickly. Jeanne Moreau, who Welles called “the greatest actress in the world,” has a short but memorable role as Doll Tearsheet. Smaller roles include Norman Rodway as Hotspur, Fernando Rey as the Earl of Worcester, Alan Webb as Justice Robert Shallow, and Michael Aldridge as Pistol. Oh, and Sir Ralph Richardson, probably the second greatest male Shakespearean actor, provides narration from Holinshed’s Chronicles.

Dame Margaret Rutherford as Mistress Quickly

Jeanne Moreau as Doll Tearsheet

Norman Rodway as Hotspur

Fernando Rey as the Earl of Worcester

Alan Webb as Justice Robert Shallow

Michael Aldridge as Pistol

The movie only has two small strikes against it: sound quality and pacing. The film was shot in Spain on a low budget and Welles couldn’t afford great recording devices, so sound quality on the set was very poor. Most of the film’s audio was dubbed in during postproduction, which is why the words are sometimes out of sync with the actors’ mouths. But even the postproduction audio wasn’t very good. Janus Films, which has a close partnership with the Criterion Collection, restored the film in 2016: the picture quality is great, but they could only improve the bad pre-recorded sound to a certain extent. But everything is in context: the film sounds way better now than it did during its release in the 1960s.

Pacing issues occur in the second half of the film, but this has more to do with Shakespeare than Welles himself. The movie’s first half takes almost all its scenes from “Henry IV Part 1,” which is a very fast-paced play with great drama, witty comedic scenes with Falstaff, and culminates in the Battle of Shrewsbury. In my opinion, it's Shakespeare’s best History play. Welles includes a few scenes and lines of dialogue from “Richard II” and “Henry IV Part 2” in the first hour, but always manages to keep a swift pace.

As an aside, some of the dialogue from those other two plays make more sense dramatically in the continuity of Welles’s films than in Shakespeare. For instance, about 20 minutes into the film, Gielgud’s Henry IV asks members of his court to find Prince Hal (“Can no man tell me of my unthrifty son?”) as he explains what reckless activities his son has been up to. In Shakespeare, this scene is at the end of “Richard II” and is meant to segue into “Henry IV Part 1.” The only issue is we’ve never met Prince Hal in “Richard II,” so Henry is telling the audience what the prince is doing rather than showing. Welles, however, places this scene after Prince Hal’s robbery at Gad’s Hill, providing the audience context for his actions.

Welles also places a scene from “Part 2” in the first half of the film: the scene in which Justices Robert Shallow and Silence present recruits to Falstaff, who signs them into the army to fight the rebellion led by the Percys. This scene in Shakespeare takes place long after the Battle of Shrewsbury and after the Percys are dead. But Welles places this scene before the Battle of Shrewsbury, which makes more sense because we understand the king needs men to fight while also providing comic relief before the battle.

Both these scenes are shot and staged in a way that could never be done in the theatre. The robbery at Gad’s Hill makes excellent use of the Spanish forest, and the way the characters run between the trees is cartoonishly funny. The scene with Shallow and Silence gives us closeups of the motley recruits they’ve assembled for Falstaff. Both sequences provide comic relief after scenes in the court and the Percys' plans for rebellion, and as a comedic reprieve before the Battle of Shrewsbury.

Much has been written about Welles’s staging of The Battle of Shrewsbury, which serves as the film’s midpoint. I think it’s safe to say the battle scene in “Chimes at Midnight” was, along with Kurosawa’s fighting scenes in “Seven Samurai,” one of the first modern action sequences. Welles himself said the film represented the death of “Merry England” and the birth of the bleak modern age. The battle scene shows this devolution from the age of chivalry into a dingy, dog eat dog world. The scene masterfully illustrates the chaotic nature of war and battle: after both sides charge at each other, we’re thrown into hand-to-hand combat and have no idea who is fighting who. The camera quickly cuts to different people fighting each other; the editing is almost reminiscent of the shower scene in “Psycho” because of how fast the cuts are. Welles’s daughter Beatrice said her father believed the battle scene in “Chimes” was the greatest sequence he ever filmed. It’s not hard to see why, nor is it difficult to understand how much the battle scene influenced later filmmakers: Mel Gibson, Kenneth Branagh, and Stephen Spielberg all used this scene as inspiration for the battle scenes in “Braveheart,” “Henry V,” and “Saving Private Ryan” respectively.

The movie’s second half takes most of its scenes and dialogue from “Henry IV Part 2,” which is a much slower play, and the comedy doesn’t hit as hard as "Part 1." The best part comes at the very end in Act 5, scene v, when Prince Hal is crowned Henry V and banishes Falstaff. It’s one of the most chilling scenes in Shakespeare, and Welles does it justice in the film. But there’s a nearly 40-minute period between the Battle of Shrewsbury and Henry V’s coronation that is filled with slower scenes. Welles plays them up further by having the characters act in a very melancholic manner; this is deliberate since time is catching up with everyone, but I think it slows the pacing. There are some great moments like Falstaff’s quick scene with Robert Shallow and Justice Silence, and Gielgud’s beautiful soliloquy, but the pacing slows down significantly. Again, this isn’t Welles’s fault since the only logical point after the Battle of Shrewsbury is to head straight into “Henry IV Part 2." It’s a great play, but I've always felt “Part 1” is far more engaging. The slow pace of the film’s second half is not bad, it just feels a little strange after a fast first half.

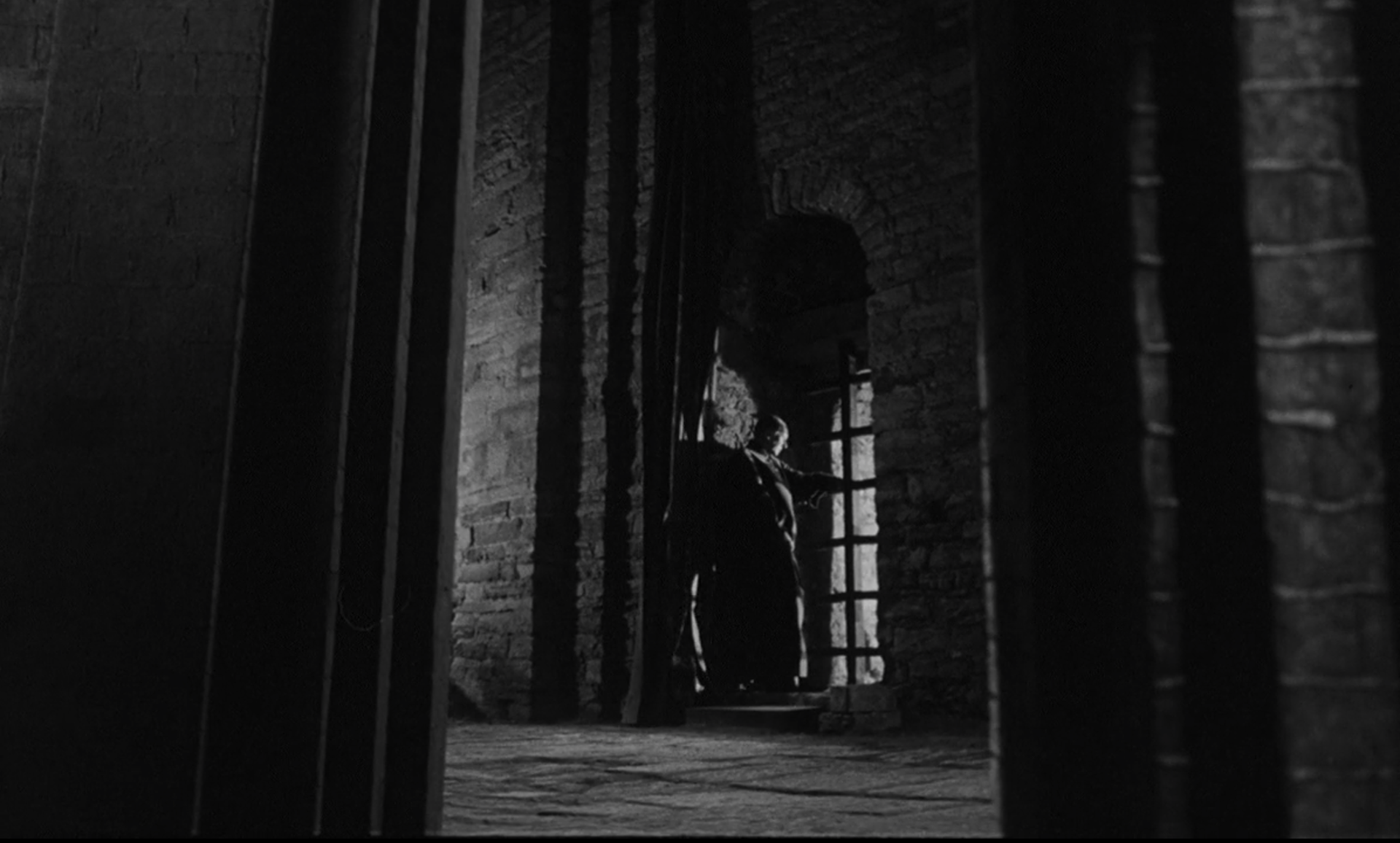

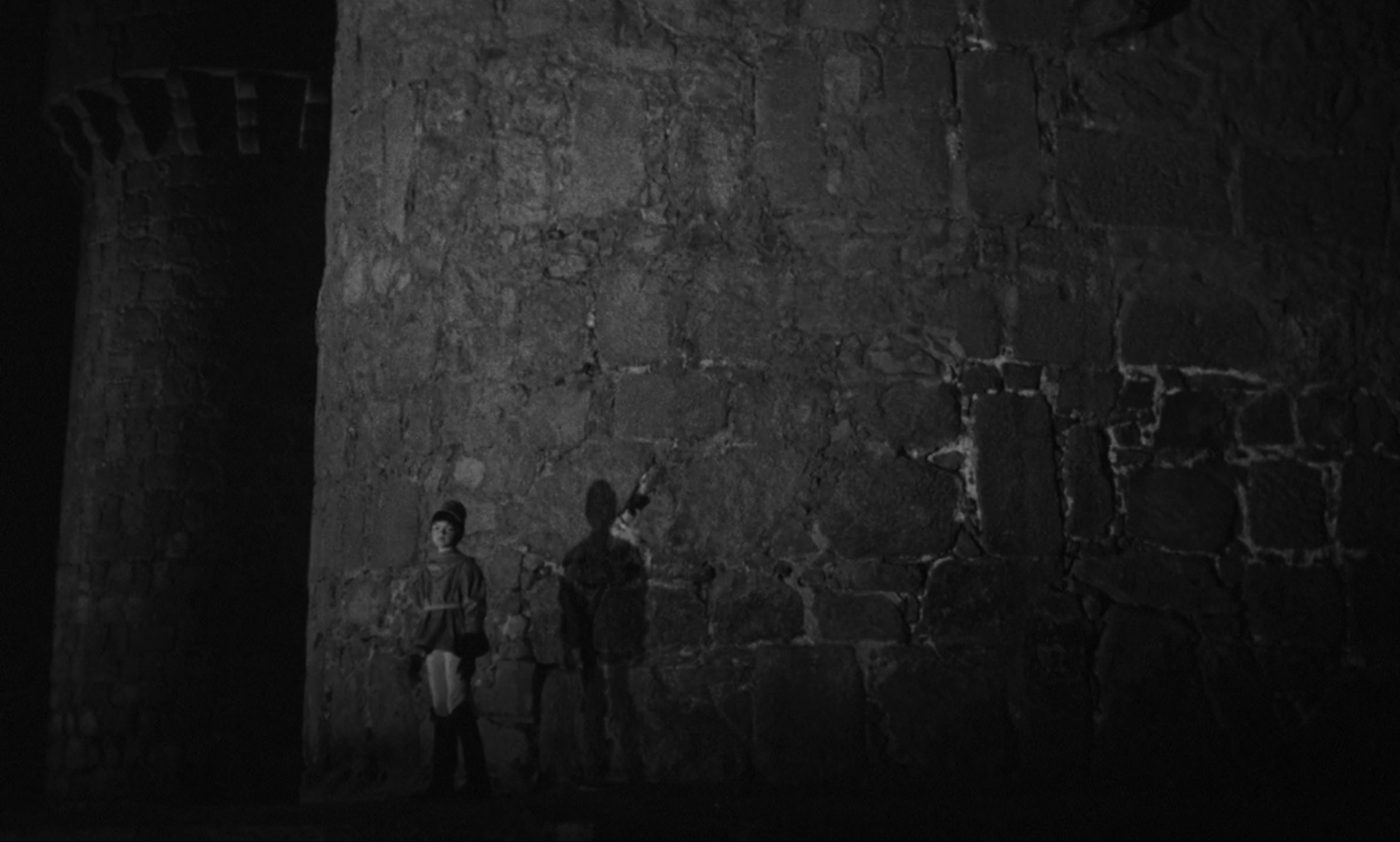

While the pace may not always be consistent, the cinematography is. “Chimes At Midnight” is Welles’s second most beautiful film after “Citizen Kane.” This is because it was shot on-location in Spain, which allowed Welles to use medieval castles and towns that hadn’t been modernized yet. I usually prefer films shot on sound stages because the complete control over sets and lighting creates amazing atmospheres. But there is something to be said for location shooting and being at the mercy of the elements around you. A set could never create the huge, interior vertical halls of Castell de Cardona (Henry IV’s castle in the film).

Sets couldn’t create the smoky fog on the muddy, grime-filled battlefield, or the walls of London in the movie—which are really the Walls of Ávila, Spain.

The streets of “old London” in the film were shot in the medieval town of Calatañazor, Spain.

The interior of Henry V’s coronation scene was filmed at the Monastery of Santa María de Huerta, and the fascade of “Westminster Abbey” at the Church of Santo Domingo, both located in Soria, Spain.

These stunning locations provide an authenticity that film sets never could. Even the cold weather evokes a melancholy that can never be mimicked in a studio: something so simple as seeing the actors’ breath when they speak evokes an amazing atmosphere. Welles clearly had an uncanny ability to use locations, the weather, and natural light to his advantage. Nowhere is this more evident than in “Chimes At Midnight.”

"Chimes" is also one of the best-lit films I've ever seen, and much of this boils down to the locations. Lighting is very hard to describe and even harder to get right. Orson Welles is one of the few filmakers who truly understood lighting. Watch any of his films, be it "Citizen Kane," "The Magnificent Ambersons," "Lady From Shanghai," "Touch of Evil," or even his later films like "F For Fake," and one thing becomes clear: he knew how to compose a shot and light it perfectly. In "Chimes," the best-lit scenes are those in Henry IV's castle due to the high contrast. If you watch the film, notice the individual beams of light pouring into the castle. Welles's decision to shoot on location using Romanesque and Gothic buildings like Castell de Cardona clearly paid off. The lighting results are breathtaking. Even on sets like the Boar's Head tavern, he uses light from fires and candles to create a high-contrast atmosphere.

The locations Welles chose provided great contrast not just in terms of lighting, but blocking and staging. I never noticed this until listening to the commentary on the Criterion Collection, but Henry IV’s castle is shot from lower angles—creating striking vertical images—whereas the Boar’s Head Tavern is shot at eye level, creating horizontal images. The verticality of the shots in the castle reinforces the power of the court, whereas the horizontal shots in the Boar's Head invokes a more down-to-earth atmosphere.

Welles’s use of nature, fog, and lighting is beautiful. It creates an atmosphere that would be impossible on a theatrical stage. Shots contrast the warmness of the Boar’s Head Tavern with that of Henry IV’s castle where we can see characters’ icy breath in the chilly atmosphere. The scenes of natural outdoor sunshine in the film’s first half are juxtaposed by rain, cold, and icy frost in the second. The turning point is the Battle of Shrewsbury, which Welles shot in a park in Madrid for 10 days in December. He shot most of it after a rainstorm, which is why the ground is so muddy and sludgy during the battle scene. Again, just seeing the war horses’ breath or people marching through the fog adds a strong sense of realism and authenticity. The forests, fog-laden fields, and wintry landscapes combined with the medieval buildings in Spain not only evokes what life was like during the Middle Ages but makes “Chimes At Midnight” one of the most authentic period pieces. o.n film.

As for the weather, Welles uses it expressionistically. The weather doesn’t always make sense in the film’s continuity. This is due to shooting delays as Welles always had trouble financing his later films; “Chimes” was an independent movie with Spanish and Swiss financing but shooting stopped multiple times for several months as Welles searched for additional money.

Due to these hiatuses in shooting, some actors weren’t available when filming resumed. Welles got around this by shooting the actors’ doubles from behind or in deep shadow, yet he edits the film so brilliantly that we the audience never notice. During the breaks in shooting, Welles usually got the money by taking acting gigs. According to the man himself, the hilariously famous (or infamous) “Frozen Peas” blooper clip happened during one of the interims as he tried to complete “Chimes At Midnight." This may be apocryphal since no one knows the exact year the audio clip was recorded, but I think it adds to the myth of this great film.

Welles was able to finish shooting when Harry Saltzman, one of the producers of the James Bond franchise, put up $500,000 to finance the picture. Before the Criterion Collection released the film on DVD and Blu Ray in 2016, it was nearly impossible for people to see “Chimes At Midnight.” This is partly because Harry Saltzman distributed the film unevenly in the United States. It received poor reviews when it was released in the US, but in Europe it was screened at the Cannes Film Festival where it won the Palme D’Or.

Today, “Chimes At Midnight” isn’t very well-known. Only film critics, Welles completists, and Shakespeare enthusiasts are aware of it. It’s too bad the general public doesn’t know about this film because it’s not only one of the greatest Shakespearean movies ever made, but one of Welles’s. Orson Welles said about “Chimes” in an interview: “If I wanted to get into heaven on the basis of one movie, that's the one I would offer up.” Considering this is the same man who made “Citizen Kane,” that’s really saying something. If “Chimes” were more well-known, I think it would easily rank among the best movies of all time.

Because this is such a gorgeous film and Welles arranges each shot perfectly, here is a gallery below: