Copyright of Universal Pictures

Disclaimer: this review contains spoilers and will be even longer than usual because there is so much going on in this movie.

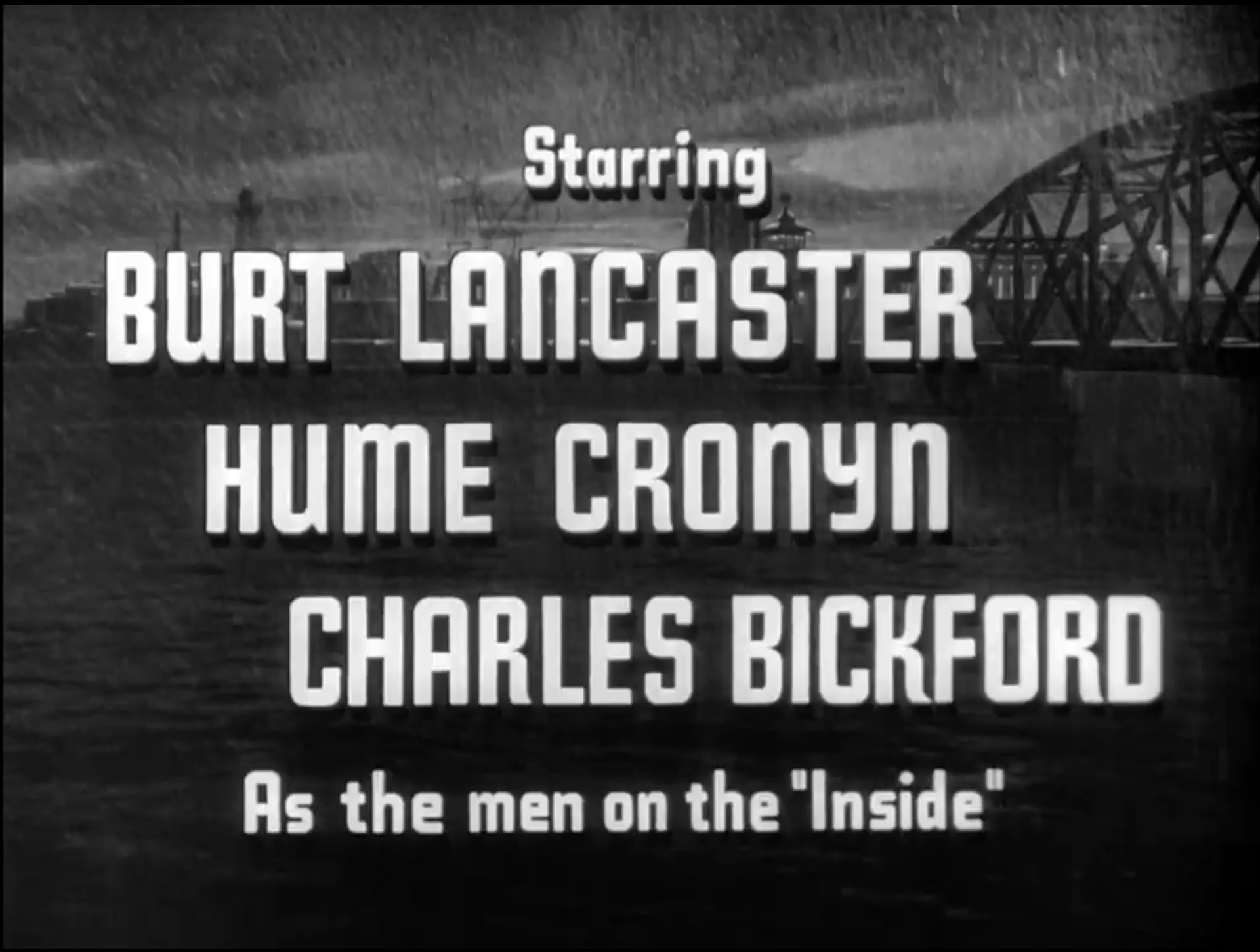

Brute Force is one of my favorite films of all time, easily in the top 10. It's a 1947 noir about a group of prisoners led by Joe Colins (Burt Lancaster) who are trying to escape a ruthless penitentiary under the control of the sadistic Captain Munsey (Hume Cronyn).

Brute Force is a great film that masterfully lives up to its title. It’s one of the best noir and prison films ever made respectively. While it doesn’t tug at one’s heartstrings like The Shawshank Redemption, it isn’t supposed to. It’s a pulpy melodrama and what it lacks in subtlety is made up in substance.

The reason it works so well is because all the elements play beautifully off each other: noir and expressionist shots combined with a melodramatic script by Richard Brooks and Miklós Rózsa’s bombastic score. Add some great performances and historical significance, and you have yourself a fantastic movie.

At the time this film was released, it became very controversial for its intense violence. While films have certainly become bloodier and more graphic, Brute Force’s violence remains intense and hard-hitting due to fast-paced editing. More on that later.

Background

Brute Force was one of the last films produced by Mark Hellinger, who was one of the first great independent producers. Hellinger worked as a New York journalist and Broadway columnist writing theatre reviews before becoming going to Hollywood. It’s believed he had around 18 million readers per week as a columnist, making him one of the most respected reviewers in the United States at the time. His career as a producer began in the late 1930s when Warner Brothers brought him in to make their gangster films more authentic. As a journalist, Hellinger had interacted with New York’s criminal underworld in the 1920s and ‘30s and helped produce films like The Roaring Twenties (1939) and Brother Orchid (1940).

Mark Hellinger in a publicity still for "Brute Force" with "the women on the outside." From left to right: Ella Raines, Ann Blyth, Mark Hellinger, Yvonne De Carlo, Anita Colby.

Hellinger embraced the noir movement when he moved over to Universal where he became an independent producer, which was rare for the 1940s. He’d previously produced another noir film in 1946, The Killers, which was a big hit and featured Burt Lancaster in his film debut. The producer always took credit for discovering Lancaster, and this second collaboration launched the new actor to stardom.

Hellinger always enjoyed telling stories about what he saw as everyday people—the man in the street. He featured stories about the “average” guy in many of his articles as a journalist and in films like The Killers, this film, and later on The Naked City and Criss Cross.

Hellinger got the idea for Brute Force from Robert Patterson, an ex-con who was out of work. Patterson had been a reporter but was convicted of check forgery and served time in the Louisiana State Penitentiary. Patterson asked Hellinger for a job. The producer agreed and loaned the ex-con a typewriter and paid for a hotel room. It wasn’t long before Patterson created the story that would become Brute Force.

Hellinger hired Richard Brooks to write a screenplay based on Patterson’s story. He had Brooks stay at an Atlanta prison for 2 weeks to study prisoners and get a sense of dialogue.

I provide all this information to illustrate how Hellinger was a very hands-on producer. Since the studios gave him freedom, he could choose whoever he wanted to direct, write, act, and compose the score without having to go to the higher-ups. He chose to work with the same people over and over again—indicative of his theatre background—and formed what was basically a film stock company.

Hellinger continued to produce noirs until his premature death at the end of 1947 at the age of 44. After Brute Force, he made The Naked City (1948) and Criss Cross (1949), both of which started the trend of docu-noir. The Naked City was shot all on-location in New York and later noir films like White Heat (1949) were shot in actual prisons and in LA. Brute Force was made entirely on a soundstage. The film has some great long shots, which were much more manageable in a studio setting and gave director Jules Dassin more control.

Jules Dassin discussing the script with Burt Lancaster, John Hoyt, Whit Bissel, and Jeff Corey.

Director Jules Dassin giving direction to Hume Cronyn and Sam Levene.

One of the sound stages for Brute Force, showing the elaborate prison set.

Jules Dassin in 1945

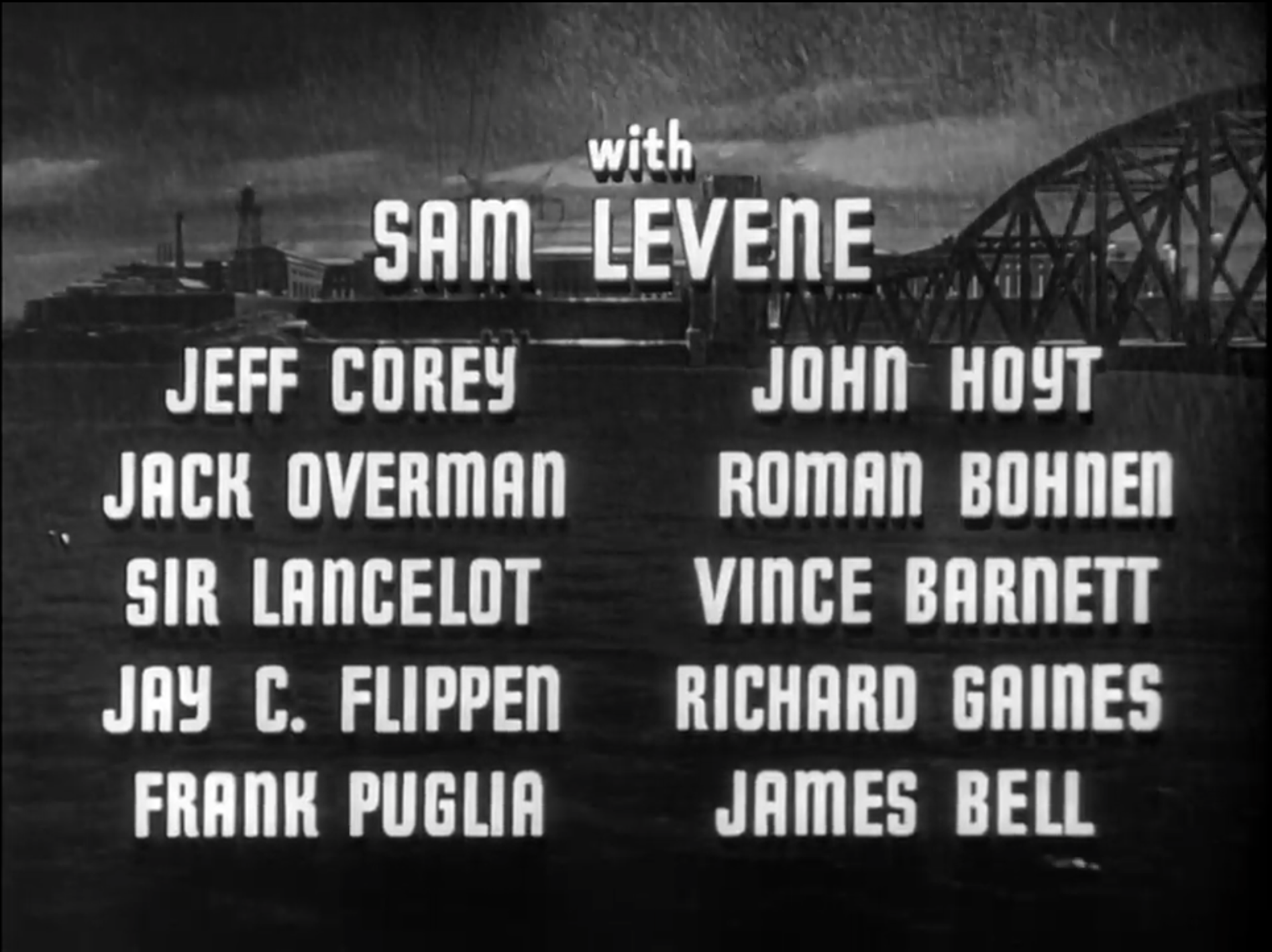

Jules Dassin got his start in as an actor in Yiddish theatre before directing feature films. By 1947 he’d made a few flops and B-Pictures and was planning on going back to the theatre when Mark Hellinger brought him on to direct this film. He’d previously worked at The Actors’ Laboratory Theatre in Los Angeles with a number of actors featured in this film including Hume Cronyn, Jeff Corey, Art Smith, and Roman Bohnen.

Dassin wasn’t thrilled with the script for the film, which he thought was silly in its depictions of women and portraying the prisoners as innocent victims of Captain Munsey. But he realized directing an A-Picture could turn his fortunes around, and it did. After Brute Force he directed The Naked City for Hellinger and Thieves Highway (1949), making him one of the most respected directors of the late 1940s.

Unfortunately, his success in America was short-lived. He was blacklisted in the early 1950s for having joined the Communist Party (CPUSA) as a young man in the 1930s, although he left the Party after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in 1939.

After his blacklisting, Dassin moved to Europe where he became a leading auteur filmmaker. His most remembered film is Rififi (1955), which he wrote, directed, and acted in. It’s considered the father of all heist films and Dassin earned the Best Director prize at the Cannes Film Festival that year.

Dassin’s blacklisting was reflective of the noir movement as a whole. A lot of people don’t realize that postwar noir was a political artistic movement. It was formed from a left-wing ideology and unfortunately a lot of those involved were blacklisted during the Second Red Scare and McCarthyism. Dassin, Roman Bohnen, Art Smith, and Jeff Corey were all blacklisted several years after this film came out.

Richard Brooks’ script places the prisoners as victims of an authoritarian, fascistic totalitarian regime in the prison system, with Captain Munsey acting as a sort of SS guard. Brooks and Dassin had always been politically motivated, and although Dassin wasn’t fond of the melodramatic script, he loved the film’s themes. He and the rest of the United States had just fought a war against fascism and authoritarianism, yet many left-wing Americans returned home to find a more right-wing government. Gone were the days of Roosevelt and the New Deal, and in were Truman, Eisenhower, and a crackdown on left-wing ideology.

This political nature becomes important as the film revolves around themes of selflessness and working for the greater good vs. selfishness and individualism. Since this has a left-leaning overtone, it embraces the former. The film is a metaphor for what Brooks and Dassin saw as the creeping fascism that was overtaking America after the war.

Review

First thing's first: if you haven't seen the film, please go watch it. I beg of you. The background information is good to have going into the film and from here on out, there are heavy spoilers. Do yourself a favor and watch Brute Force if you haven't already.

You should be able to tell everything about a film in its opening titles. Brute Force is a masterclass at this: the first shots of rain dripping from the tower of Westgate Penitentiary before transitioning to an overview of the island prison as Miklós Rózsa’s bombastic score picks up. I get chills every time the opening theme plays.

Rózsa was one of the greatest film composers of all time and made a huge impact in other noir films like Double Indemnity (1944) and historical epics such as Quo Vadis (1951), Julius Caesar (1953), and Ben-Hur (1959). His opening score begins with screaming violins before blaring dramatic brass. It’s a great indicator of the melodrama and violence to come.

Rain is a common visual theme in noir, and we see it in full force as it batters the prison. The title sequence is somewhat unique for this time period because the rain provides motion, whereas most title sequences were on static title cards.

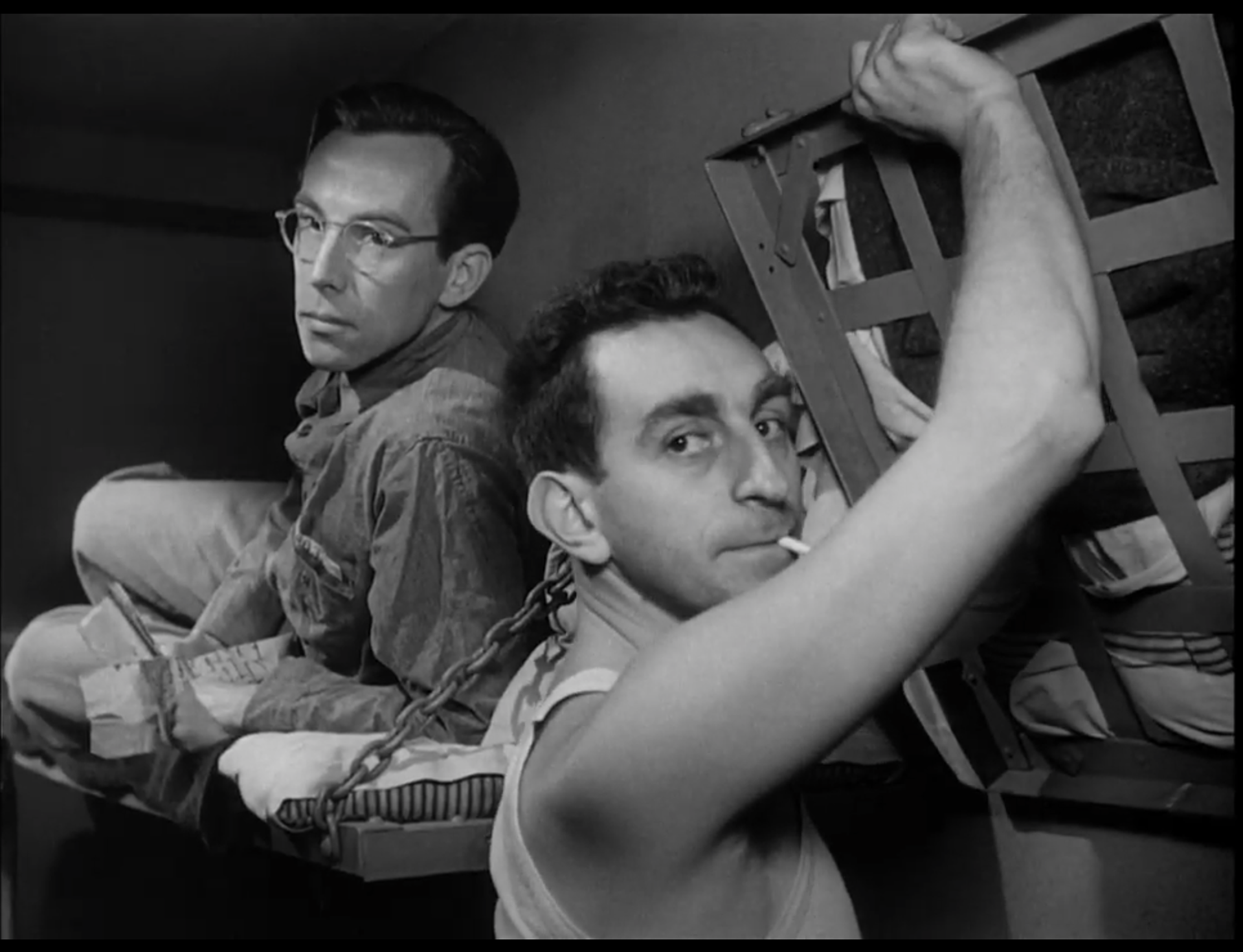

The first shots inside the prison gives us a quick rundown on who’s who. In one cell there’s Gallagher (Charles Bickford) and Louie Miller (Sam Levene). Gallagher acts as the prison’s fixer, like Red from Shawshank Redemption. His cellmate Louie is an informer who helps Gallagher run the prison newspaper. As a reporter, he’s allowed to go anywhere in the prison and secretly spreads news to other inmates.

Next there’s Calypso, played by Sir Lancelot. Calypso acts as the Greek Chorus, singing events as they occur. Sir Lancelot was a calypso singer who popularized the genre in the US. His character adds a break to most of the intensity—not levity, but a short reprieve as he announces what’s going on.

The main characters are all in cell R-17. There’s Spencer (John Hoyt), a con man, gambler, and intellectual; “Soldier” Becker (Howard Duff), a WWII veteran; “Freshman" Stack (Jeff Corey); Tom Lister (Whit Bissel); and Kid Coy (Jack Overman). Kid Coy is a replacement since one of their cellmates, Frank McClain, died after Captain Munsey put him to work in the drainpipe.

John Hoyt as Spencer

Howard Duff as "Soldier" Becker

Whit Bissell (left) and Jeff Corey (right) as Tom Lister and "Freshman" Stack

Jack Overman as Kid Coy

Sir Lancelot as Calypso, who's in the cell next to R-17

Captain Munsey (Cronyn) is introduced with another guard escorting Joe Collins (Lancaster) back to his cell after a stint in solitary confinement. Joe was caught with a shiv that was planted on him. We first get a sense of Munsey’s cruelty as he emotionally jabs Collins with the loss of his friend and cellmate, who only had eight months left to serve. “Knowing McClain, out in eight months, back in nine, right Collins?”

Hume Cronyn as Captain Munsey and Burt Lancaster as Joe Collins

Once Joe is escorted back to his cell, we get an immediate sense of the camaraderie between all the cellmates of R-17. They’re his friends—they ask him how he is and light his cigarette for him. But Joe isn’t having any of the friendship. Solitary apparently changed him, because he’s now determined to break out with his pals.

Joe wants to get out so he can help save his girlfriend’s life. She’s dying of cancer and can be saved with an operation, but she refuses to get it until Joe is with her. He says he only wants to break himself out and doesn’t care about the others, but that clearly isn’t the case. Throughout the film we see him show compassion and care for his fellow inmates.

And that’s basically the entire plot: tension builds between the prisoners and Munsey as Joe tries to convince Gallagher to help get supplies to break out.

The main draw of this film is its characters. The camaraderie between the cellmates is very genuine, which is something we don’t always see in prison movies. There’s no machismo or toxicity. These are men who clearly love and respect one another and would do anything to help. They all welcome Kid Coy, the newest cellmate who replaced McClain, and immediately embrace him as one of their own.

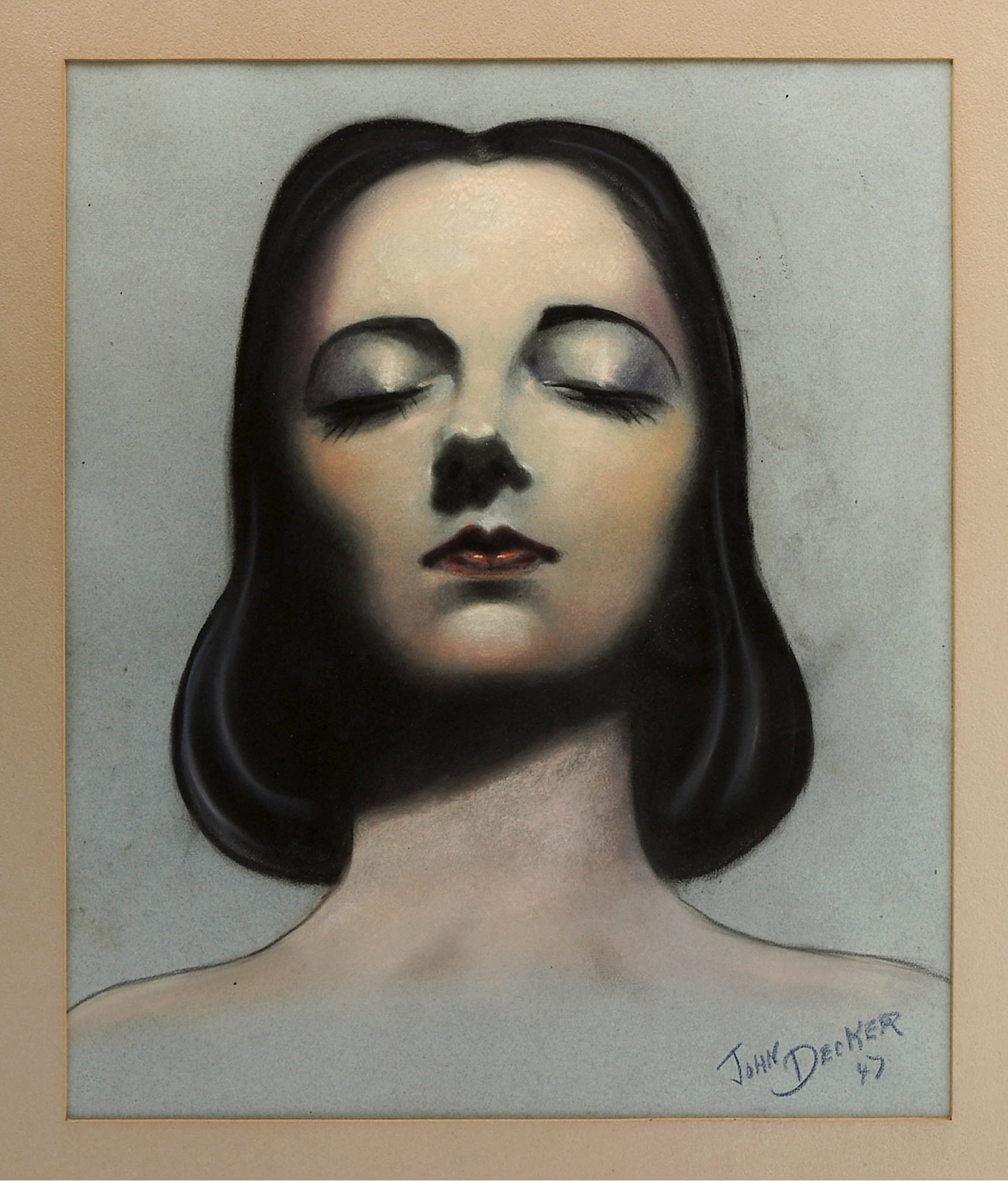

The scenes in the cell are all great, especially the ones leading into flashbacks. Kid Coy asks why they keep a strange pinup of a calendar girl.

“That’s no ordinary pinup girl. To each one of us, she’s someone special.”

John Decker painted the calendar girl for the film.

The calendar girl serves as a lead-in to all of the flashbacks, which are mini-movies in of themselves. Each one could easily be a film of its own as it reveals how the men ended up in prison. Each flashback revolves around a woman, which is very noir. The calendar girl symbolizes the femme fatale, a stock character that popped up in most noir films.

The flashbacks start where most noir movies end: with the downfall of the main character. In this case, the main character is whoever is remembering their own story.

The first flashback is Spencer’s (John Hoyt) and is the most lighthearted and my personal favorite. A lot of it has to do with Hoyt’s delivery, which is whimsical and nostalgic as he recounts how a woman beat him at his own con game. Hoyt was a great character actor who popped up in over 200 films and tv shows, including The Conqueror with John Wayne, which probably contributed to his cancer later in life.

Hoyt’s flashback sees Spencer at an illegal gambling operation with a woman he’d met named Flossie. The police raid the joint, but Flossie helps him escape to his car. As they’re driving, she turns his gun on him, forcing Spencer to hand over the car and cash he’d won. “I wonder who Flossie’s fleecing now,” he reminisces.

There are tons of great lines in this film, and John Hoyt’s short flashback has some wonderful ones. I’ve put a few in the gallery below:

“The dice were hot, and she kept them that way.”

“Leave it to the police to break up a wonderful evening—it looked as though everybody was caught with their chips down.”

“Flossie had looks, brains, and all the accessories. She was better than a deck with six aces!”

She was not only beautiful, she knew the score as well.”

“She wanted all the money I’d won, and I never refuse a lady—especially when she’s armed.”

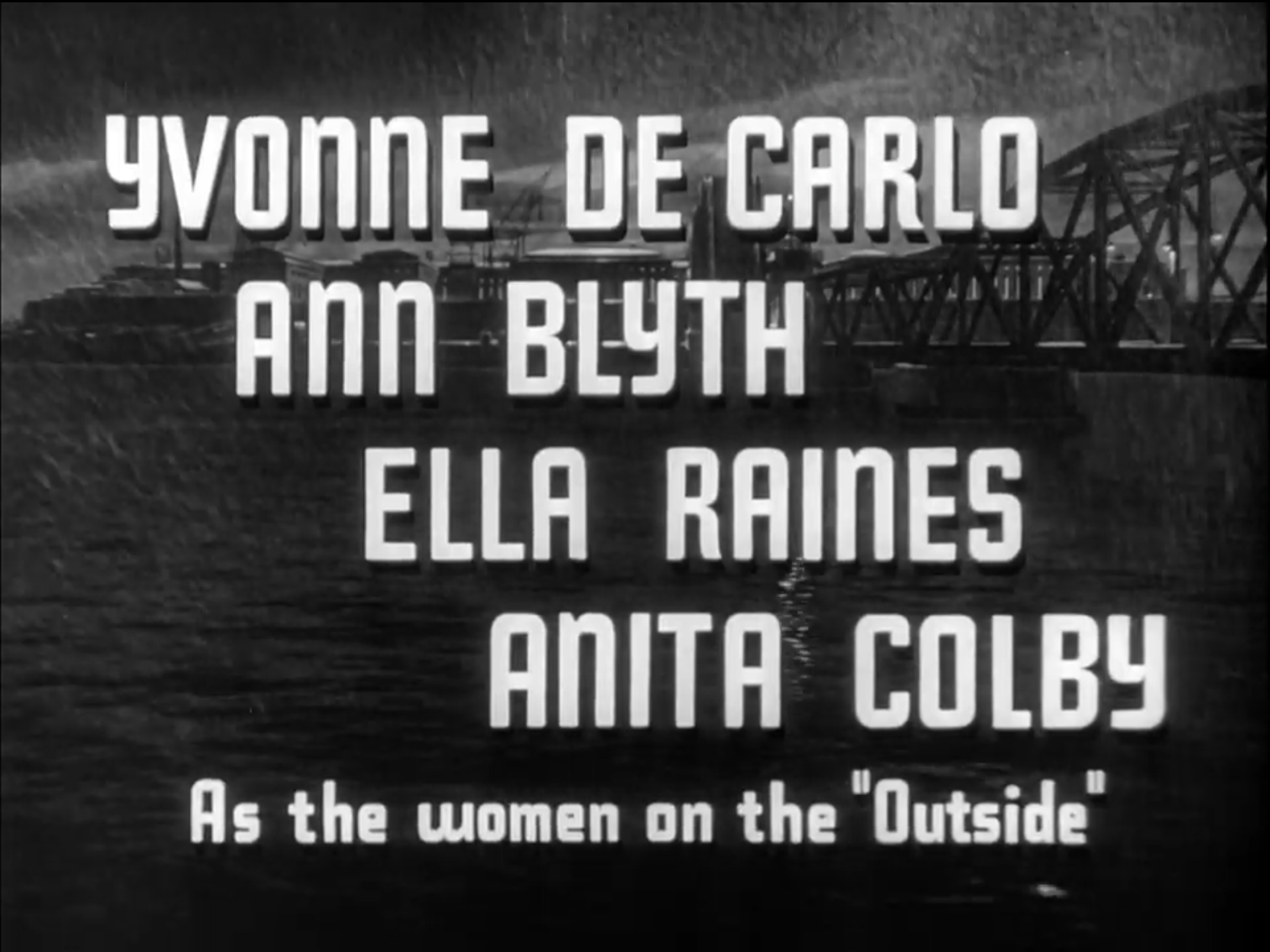

Less effective is the flashback between Tom Lister (Whit Bissell) and Ella Raines. Ella Raines is great as always and was a staple of noir, appearing in films like The Phantom Lady and The Suspect. Whit Bissel is alright. It’s not his fault, as he has little screen time and we don’t know the full story behind the flashback, which doesn’t have the same great dialogue as John Hoyt’s. The flashback shows Lister come home from work and gifts a fur coat to his wife. She realizes they can’t afford it and it’s revealed he stole $3,000 to help her afford the things she wants.

The next flashback occurs later in the film and shows “Soldier” Becker (Howard Duff) in Italy during the war. He’s fallen in love with an Italian woman, Gina (Yvonne De Carlo), but her father threatens to report them to the Italian police. Gina shoots her father to prevent him from turning them in, and Becker takes the rap. I know I sound like a broken record, but this one really has a noir ending with Gina killing her own father. It was relatively rare to see women committing murders on screen at the time and noir and horror were the only two genres to show it.

Joe’s flashback is the most emotional and sincere. After pulling a job, he returns to his girlfriend, Ruth (Ann Blyth), who’s dying of cancer. She’s an invalid, and Joe’s brought back money (presumably from the heist) to pay for an operation that will help her walk. He can’t stay long but says he’ll be back, and the next time will be the last. Clearly he’s run off before when delivering the money, probably to keep the police off him. But one more job and he’ll have enough to help her.

This is the most sentimental of the flashbacks as we see they clearly love each other. Ruth asks him why he loves her. “Why?” she asks. “I’m sick, Joe, why do you love me? When you’re sick, people don’t really love you, they only feel sorry for you.”

“I’m not people. I’m Joe Collins . . . There are all kinds of sick people. Maybe we can help each other.”

It’s a nice short, little scene, and it’s nice to Lancaster’s change in performance. Here, he’s enthusiastic, filled with love. He smiles and holds himself upright. In the rest of film behind bars, Lancaster's Joe Collins is beaten down and walks in a defeated posture. His eyes stare out coldly. It’s great to see the character before his incarceration.

All of the flashback scenes humanize the prisoners of R-17. We don’t see flashbacks for “Freshman” Stack or Kid Coy, but the ones we do get emphasize the prisoners as human beings, not numbers.

I mentioned earlier that Jules Dassin felt the inmates came across as too innocent. I disagree. Their humanization in the flashbacks adds complexity when we are shown firsthand these men can be cold-blooded killers as they mete out brutal prison justice.

One rule of the prison is don’t be a snitch. The morning Joe Collins gets out of solitary, there’s a scene in the mess hall where it’s revealed there’s going to be a hit on the man who put him there. Wilson is the inmate who planted the shiv on Joe that caused him to stay in solitary. We see Wilson pleading with his fellow inmates to fix the situation. He goes to Gallagher and Louie and begs for help. We get this nice little exchange:

Louie [to Gallagher]: Wilson. He’s here on the 529, also a stoolpigeon. He planted the shiv on Collins.

Wilson: Munsey made me do it, honest. You can fix anything, Gallagher. If you can call off Collins, I can pay I’d—

Gallagher: You’ll pay.

Suddenly the mess hall gets quiet. We see Captain Munsey and another guard enter and patrol the hall. This is a great short scene illustrating Munsey’s hypocritical nature: he acts congenial towards the prisoners while plotting new ways to torture them emotionally and physically. Wilson asks Munsey for help, but the captain shrugs him off.

The cinematography in this scene is great, starting with a wide shot before cutting to several very expressionist shots. There are some nice stylized framings with Hume Cronyn’s face in the foreground, Charles Bickford in-focus in the center, and Sam Levene out of focus in the background.

This last shot of Munsey’s arm in the foreground is great.

What’s so great about this shot is Munsey’s arm is visually separating two inmates who won’t be there for Joe and the other cellmates when they need them most—Freshman Stack and Tom Lister. It’s great subconscious visual foreshadowing.

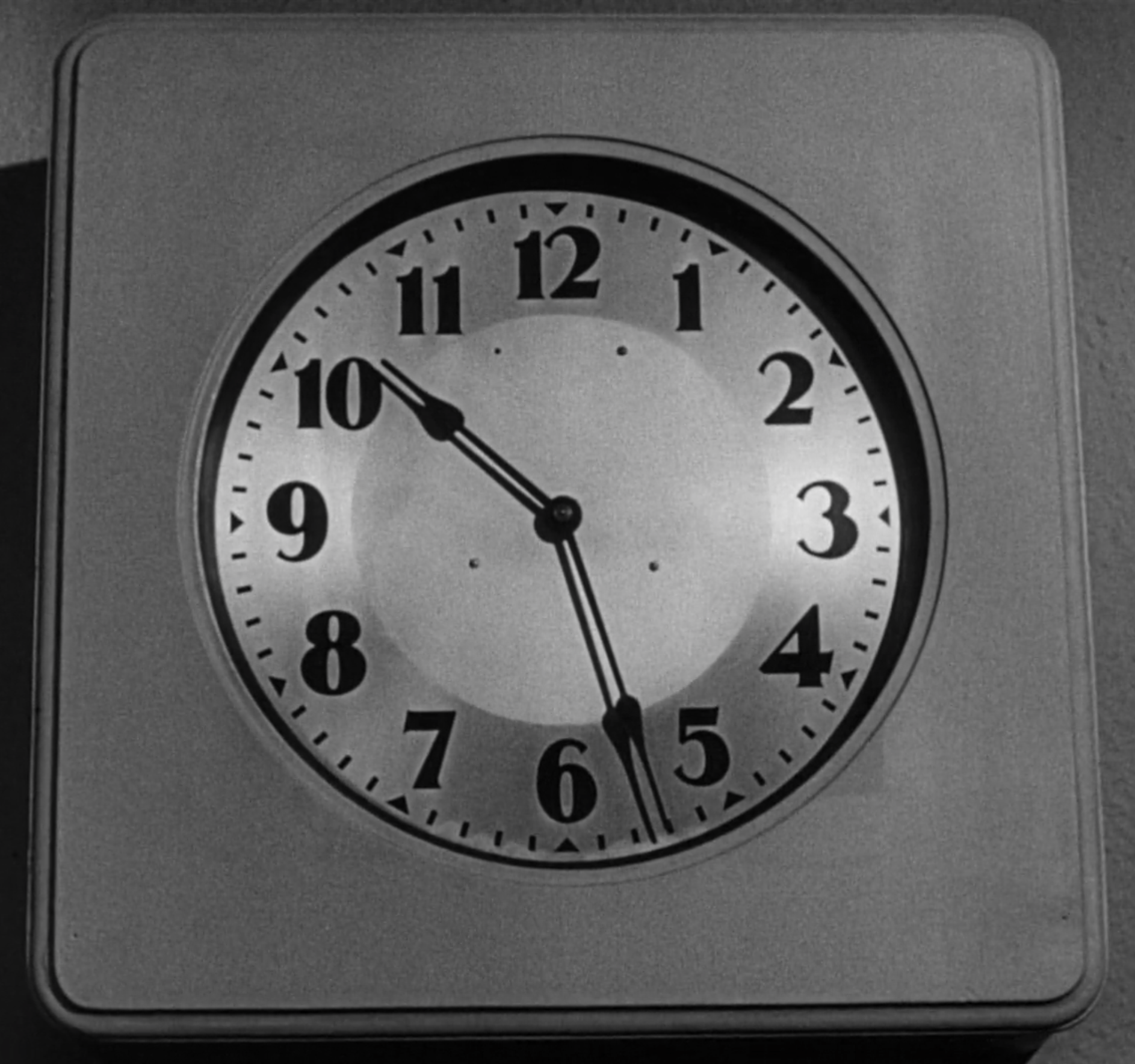

As for prison justice, we get a great scene about 20 minutes into the film with the hit on Wilson. Joe Collins is in Dr. Walters’ office to avoid suspicion. Collins asks what time it is. “About 10:30,” Walters replies. “To be exact, it’s 10:27. Why?” Joe doesn’t answer.

Meanwhile, in the prison workshop, Soldier (Duff) and Spencer (Hoyt) are going around telling everyone, “Wilson, 10:30.”

The hit on Wilson the stoolpigeon is brutal. The prisoners in the workshop cause a riot to distract the guards and bang their tools loudly while Soldier, Spencer, and Kid Coy gang up on Wilson and corner him with blowtorches. When he grabs onto a bench, they burn his fingers and back him into a machine press.

The Breen Office and film censors objected to scene in the shop. Hellinger managed to push it through and prevented it from being cut. It’s one of the most famous in the film for its brutality.

Dassin does a wonderful job of creating tension in the scene: it starts off slow as Soldier and Spencer inform every one of the hit with the soft whirring of machinery in the background. The sound gets louder and louder until the riot starts and the clanging becomes deafening.

While it’s rather tame today, it was unheard of (or rather unseen) for a premeditated death to be shown in such detail. My guess is the censors objected to the burning of Wilson with the blowtorch and the shot of the press coming down on top of him. We don’t see his crushed body, but our imaginations make it more horrifying than it could ever be on screen.

This brutal form of prison justice absolves the men of innocence. They all come off as cold-blooded during the killing. After Wilson’s death, Dr. Walters gets a call and tells Joe that the man who put him in solitary is dead. Joe doesn’t seem fazed.

In fact, Joe isn’t fazed by much throughout the entire film. It’s a testament to Lancaster’s performance, which is very understated. He has little dialogue and most of his acting is done through his body language and facial expressions.

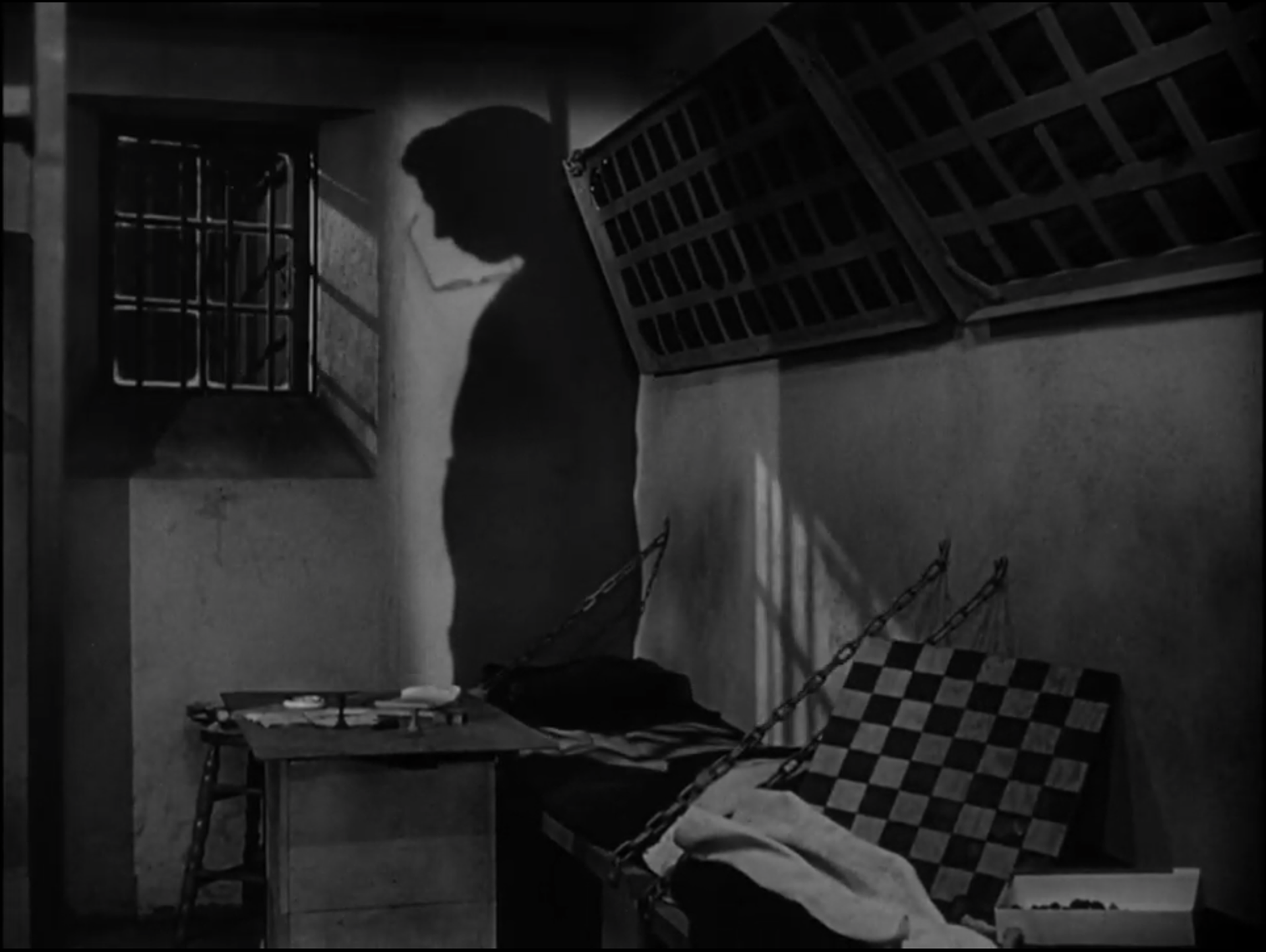

Lancaster had been a trapeze artist and acrobat in the circus before going into film. This, combined with his love of Lon Chaney Sr. and silent movie acting, allowed him to use his body and posture in unique ways. His acting has a very expressionist feel to it. We see a hint of his acrobatics when he vaults himself over his cellmates’ chess game or goes from standing to crouching with lightning speed. Of all the characters, we see how much Joe has been dehumanized by prison, courtesy of Lancaster’s performance. He stares blankly with his mouth open and walks in an even, robotic manner.

Towards the end of the film, Lancaster’s acting changes. When Dr. Walters tells him that Munsey knows of their plan to break out, we get a great close-up of Lancaster’s face: it’s completely still but his eyes dart from side to side like a trapped animal. When he and his cellmates put their plan into motion, we see a new Joe Collins: pained, angry, feral. He turns into a wild animal. We see the pained look on his face when he witnesses his friends’ deaths. When he’s shot, he unleashes his energy in a primal howl and unleashes his final fury on Munsey, lifting the puny captain over his head on the tower and throwing him to the prisoners below. As Joe dies, he sees his plan has failed and gives one final, anguished expression.

Lancaster’s been holding all his emotions in for the entire film until the end, and it’s a great payoff. Although he didn’t have the previous stage or screen experience like his fellow actors who worked on the film, Lancaster proves he didn’t need it. It would be an amazing performance by any actor, especially someone who’s only appearing in their second film.

All the supporting actors do a wonderful job illustrating their characters. We’re introduced to over a dozen characters in the first fifteen minutes of the film, and each actor makes their characters unique. Each of Lancaster’s cellmates shows us their respective characters through facial and eye movements. John Hoyt’s Spencer, the con man, squints his eyes and wrinkles his brow to show shrewdness. Howard Duff’s Soldier Becker upturns his eyes to evoke sympathy.

The portrayal of the characters working inside the prison system are just as important. Charles Bickford’s Gallagher serves as a foil to Joe Collins. Gallagher is all about serving oneself and using the broken system to one’s advantage. Even though he’s serving time, he believes the prison system works and everyone will be fine if they do what they’re told. In his case, if he obeys the rules and behaves himself, he’ll get paroled early. Unlike Joe, who fights to break everyone out (ie the common good), Gallagher only fights for himself. Gallagher refuses to side with Collins’ breakout plan for most of the film. He only realizes centrism won’t work when the Department of Defense denies all parole hearings. Then, and only then, does he side with Joe. But during the climax as the plan falters, he goes back to being his “every man for himself” mentality, which dooms the plan. If Gallagher had put the cause above himself, the break out might have succeeded. He puts himself first rather than align with the collective, which clashes with the philosophy of post-war noir, socialism, and communism.

Art Smith’s performance is pretty good. His role as Dr. Walters was his first credited performance. He’d been a member of the famous Group Theatre in New York. His character slouches and slumps in drunkenness. It’s the familiar trope of the drunken but goodhearted malcontent.

Dr. Walters presents the viewpoint of the screenwriter. He has a very anti-fascist, anti-authoritarian view and seems to be the only person who cares about the prisoners’ well-being. In his first meeting with the warden, Munsey, and a bureaucrat from the Department of Defense, he yells, “What we need here is a little more patience, and much more understanding!” His attempt to empathize with the prisoners is what makes him so endearing.

Art Smith as Dr. Walters

Roman Bohnen as Warden Barnes takes the traditional role of the warden and flips it on its head. In most prison films—be it 20,000 Years In Sing Sing (1932), Birdman of Alcatraz (1962, also with Burt Lancaster), or The Shawshank Redemption (1994)—the warden is the one with all the control and usually displays an iron will. Here, the warden is a pushover. In the warden’s first scene, the three other characters—Munsey, Dr. Walters, and McCollum from the Department of the Defense—use him as a doormat. He seems to have good intentions; Munsey says the warden wants to help the prisoners but is misguided and too compassionate.

Bohnen is great in the role. He fidgets nervously and chain smokes to ease the tension. Towards the end of the film, we see the warden come to terms with his impending forced resignation. McCollum is coming the next day to have him sign his job away. “Everything’s gone wrong. I don’t know who’s to blame,” he says forlornly. The warden only shows backbone when McCollum tells him to inform the prisoners that Munsey is the new warden, but by then, it’s too late.

Roman Bohnen as Warden Barnes

For me, the standout performance in the film (besides Lancaster) is Hume Cronyn as Captain Munsey. Cronyn is one of my favorite character actors ever and I rank this as his best performance, so I'm more than a bit biased here. He had previously worked with a few people associated with this film including Roman Bohnen, Sam Levene, Jeff Corey, and Jules Dassin at the Actors’ Laboratory Theatre in Los Angeles. His casting in Brute Force marked the only time he played a villain in his career; a shame, since he knocks it out of the park.

Perhaps part of the reason why Cronyn is so great as Captain Munsey is because it’s not an obvious casting choice. The actor had a long career of playing meek, mild-mannered characters. At 5’6”, he’s hardly an imposing physical presence. TCM’s Eddie Muller said Cronyn’s casting “[drives] home the idea that a meek, insecure man granted a bit of power and authority can quickly become a monster.” He’s absolutely right.

Cronyn’s Captain Munsey is faux affably evil, pretending to be polite and patting prisoners on the back in the mess hall scene, when in reality he’s a sadist who enjoys physically and emotionally torturing the inmates. In the mess hall scene, he prevents a guard from hitting Tom Lister after the latter crashed into him. “What’s the matter with you? It wasn’t his fault,” he tells the guard. “Sorry, Lister.”

Later that evening, Munsey drops by R-17 to see Lister while everyone else is watching a movie. He goes to Lister’s cell to apologize for the incident in the mess and offers him a cigarette, but he’s really trying to get Tom to become an informant. He tries to get Tom over to his side by implying he’ll stop censoring the prisoner’s mail.

“I get quite a kick out of censoring the mail. All these letters you write home, for example, and the answers you never get.” It doesn’t work and Tom refuses to become an informer. Munsey—infuriated for not getting what he wants— tells Tom he’s received a letter from his wife. When Tom asks how his she is, Munsey coldly tells him, “in a way Tom you’re a free man—she’s divorcing you.” Distraught, Tom hangs himself later that night.

It’s a great example of Munsey’s emotional torture.

Tom’s suicide, along with Wilson’s murder earlier that day, causes the warden to revoke all prisoner privileges. It’s hard to imagine that Munsey didn’t plan this all along.

Munsey is the film’s representation of a fascistic character. He was modeled after the Nazis that many people who worked on this film (Hellinger, Brooks, and Lancaster were in the service) fought against during WWII. As a fascistic and Hitlerian figure, he undermines the warden and creates a Reichstag moment to seize power. Due to his position as captain of the guard, he’s at least aware of the prisoners’ code and justice system; he knew that Wilson would get his comeuppance for planting the knife on Joe and emotionally manipulated Tom Lister into hanging himself. These two events stripped the prisoners of their privileges and showed the state department that the warden is too inefficient, meaning it won’t be long until he gets the power he craves.

The deaths of Wilson and Tom Lister allows Munsey to put the men of cell R-17 on duty in the drainpipe: a work facility where the worst prisoners are sent to die. The drainpipe in this film is more like a mine; we’re never told what it’s for or why it’s being built. It’s emblematic of noir’s nihilism as it leads nowhere and serves no real purpose. For further context, if Munsey is the Nazi SS guard, then the drainpipe is the concentration camp. It highlights the captain’s cruelty as a not-so-subtle reminder of the character’s representation of fascism.

Munsey is a warning sign by Brooks against what he, Dassin, and many involved in this film saw as a fascistic order coming to the United States after the war: the rise of the right wing, HUAC’s crackdown on left-wingers, and the repression of women after they’d played such a big part in the war effort. His fascist characteristics aren’t subtle, and the film makes some obvious comparisons to Hitler and the Nazis as it goes on.

My favorite scene in the film (besides the climax) is between Munsey and Dr. Walters, and it really illustrates their clashing ideologies with the captain as the Nazi-esque fascist and the doctor as the conscience. It starts out with some slightly more three-dimensional thoughts on Munsey. Warden Barnes is preparing to resign the next morning and mentions how the prisoners hate all of them.

Musney disagrees. “It’s me they hate . . . you put on a guard’s uniform and see how much they love you. You talk to the prisoners over a loudspeaker, I talk to them with a club. You only make the rules, I have to enforce them.”

After Warden Barnes leaves for the night, Munsey and Dr. Walters have a conversation in the film’s best scene. Munsey gives a monologue to a drunken Dr. Walters about power. It’s such a great scene I’m providing a transcript below:

Munsey: “I want to help the warden. It’s just that he’s confused. He doesn’t realize that kindness is actually weakness. And weakness is an infection that makes a man a follower instead of a leader.”

Dr. Walters: "It seems to me a very great leader once said, ‘the meek shall inherit the earth.’"

Munsey: "Science contradicts that doctor. Nature proves that the weak must die so that the strong may live. Authority. Cleverness. Imagination. Those are real differences between men. I walk amongst these convicts, these thieves and murderers, alone. Unarmed. They respect me. They obey me."

Munsey has revealed himself completely. He wants control and embraces Social Darwinism and the authoritarian view that rejects all kindness and compassion, putting power above all. There’s a great touch of direction as Munsey tidies up the warden’s desk: he closes folders and puts them away, places loose pencils in a tin. He’s a control freak and can’t stand to see any disorder, even a tiny amount of clutter on the warden’s desk. Satisfied, he sits himself in the wardens’ chair.

Dr. Walters psychoanalyzes him, comparing the captain to Alexander the Great, Genghis Kahn, and Julius Caesar. There are two names he’s leaving out: Napoleon and Hitler. Napoleon, or rather Munsey’s Napoleon complex, Hitler as the clear figure Munsey is imitating throughout the film.

“You’re drunk,” Munsey scoffs, with a fantastic line delivery by Cronyn.

“What makes you drunk?” The doctor retorts. “Power?”

They have a great exchange where Walters accuses Munsey of making Tom Lister hang himself. He keep psychoanalyzing Munsey until the captain knocks the doctor to the floor. Dr. Walters gets up and delivers what has got to be one of the greatest title drops in film history. It’s hardly subtle—nothing about this scene is—but it’s very satisfying. It does an excellent job of doubling down on Munsey as embodiment of authoritarianism and fascism.

Below are a few screen shots with quotes and a video link to part of the scene.

"What makes you drunk? Power?"

“Did you censor his mail? Wouldn’t he give you any information? Or did you tell him a few lies about his wife?”

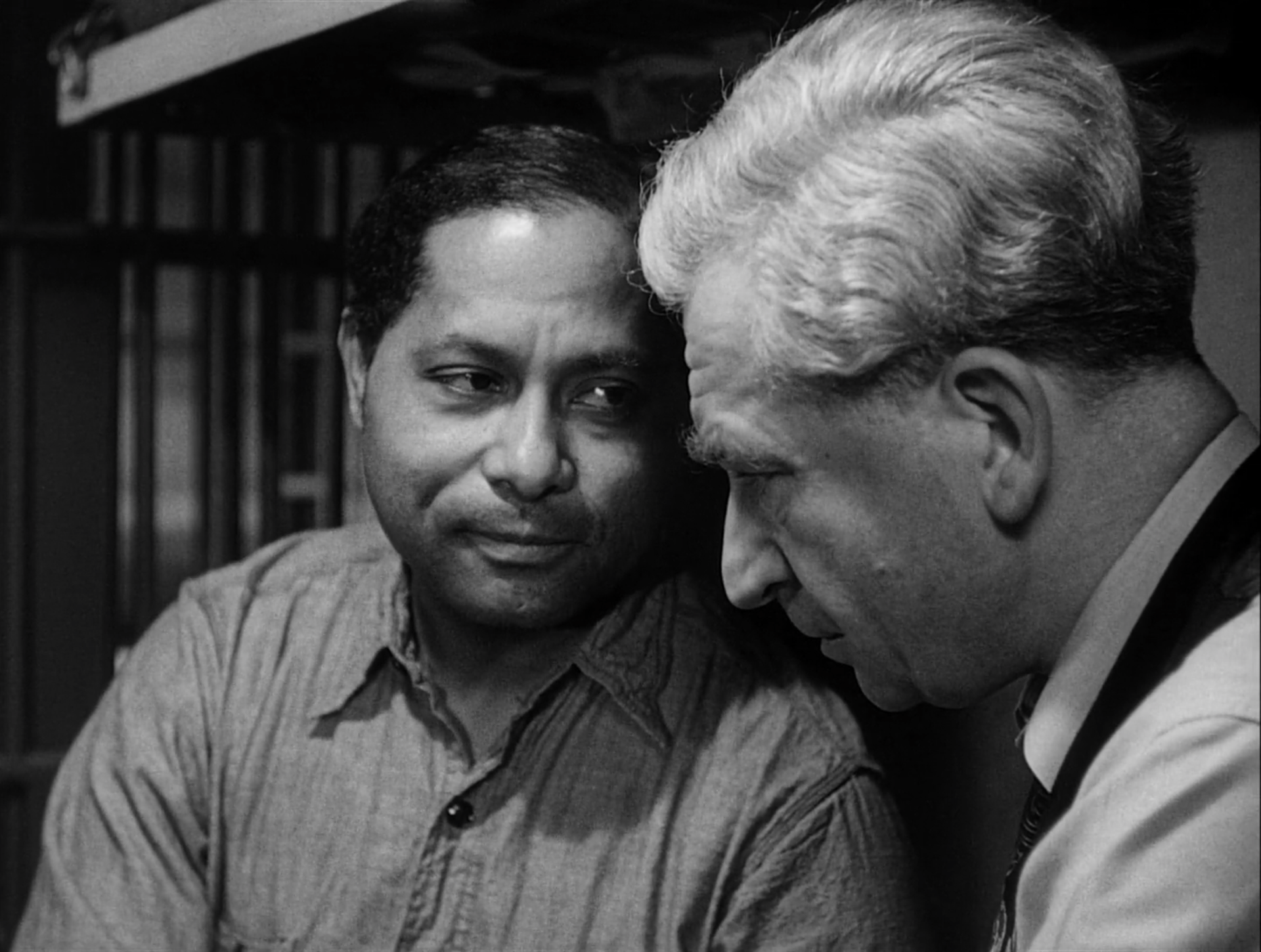

The scene that really harps on the captain’s Nazi-esque tendencies was also one of the most controversial and infamous at the time. It shows Munsey handcuffing Louie (Sam Levene) to a chair and beating him with a rubber pipe. For context, Louie and Gallagher are getting bombs, Molotov cocktails, and dynamite together to help Joe with the escape plan. The problem is they can’t get dynamite, so Gallagher tells Louie to go to the drainpipe and tell Joe there’s no dynamite for the breakout. As a reporter for the prison newspaper, Louie has clearance to go wherever he wants, except this time he’s caught and taken to Captain Munsey. The captain asks why Louie wants to go the drainpipe. “To write a story,” Louie says. Munsey already knows there’s a breakout plan, but he doesn't know if Joe Collins and Gallagher are working together to bust out. Since Louie and Gallagher are close, the captain wants to know if there's a connection between Gallagher and Joe, so he tries to beat the information out of Louie with a pipe.

Even before the beating, the introduction to Munsey in this scene furthers the fascist parallels. We see him in his office, perched on his desk polishing a rifle, his pose mimicking a statue to his left (our right). We then get a shot of another wall with a gramophone playing a record of Richard Wagner’s opera Tannhäuser and a picture of Michelangelo’s statue “The Rebellious Slave.” These images and sounds would’ve been very obvious to audiences in 1947. Hitler loved Wagner and the Nazis were fascinated with the ideal male body and drew on Classical and Neoclassical art. The symbols in Munsey’s office reminded audiences of the enemy they’d fought several years earlier.

Munsey's office, with the captain mirroring the statue on his bookshelf.

The gramophone playing a Wagner record with Michelangelo's "Rebellious Slave" statue in a photograph.

And to drive home Munsey’s fascistic nature even further, Sam Levene’s character is implied to be Jewish. Levene himself was Jewish, and he played a Jewish character who gets beaten to death in the film Crossfire (1947), which was released several months before Brute Force. Crossfire was still very fresh in the minds of audiences. So we now have Munsey the fascist beating a Jewish character. It’s hardly subtle, but knowing the context makes this scene all the more powerful and frightening.

We never see the blows, but we hear the repeated sound impact and the guards, who are outside Munsey’s office, give horrified reactions. Munsey turns up the gramophone volume and continues beating Louie as the camera cuts away. The Production Code prohibited the blows actually being shown, but they don’t need to be. In this case, less is more and the after-effect is enough to get the point across. The guards’ disgusted reactions are powerful, the cuts are sharp, and Cronyn and Levene give excellent performances in this scene. Cronyn never raises his voice, delivering his lines in with icy determination. Levene rolls his eyes into the back of his head and pants heavily, too exhausted with pain to even move.

Munsey clearly enjoys beating Louie. There’s an added psychological and mental torture at the beginning as the captain deliberately shows Louie the pipe to build a sense of dread. We see Louie squirm in his chair as he tries to prepare himself for the first blow.

Louie is loyal and doesn’t tell Munsey of the connection between Gallagher and Joe.

Dr. Walters goes to the drainpipe to tell Joe that Louie was beaten up and might die, and he has a message for Joe: “whatever your plan is, don’t go through with it. Munsey knows.” It’s then that Joe realizes one of his own men is an informer and told the captain about the breakout. To figure out who it is, he asks each of his cellmates what position they want to take during the upcoming fight. Soldier, Spencer, and Kid Coy all ay they don’t care, they’ll do whatever Joe tells them to. But Freshman Stack says he’ll take the left position because it’s the “toughest,” and by doing so reveals he’s the snitch. It’s subtle yet effective.

We then see that Munsey has an extra machine gun stationed outside the drainpipe. One of the guards puts it well: “Clay pigeons would have a better chance.” It’s clear Joe’s breakout plan won’t work.

"Just remember, there's no reward for bringing 'em back alive. Not in this jungle."

So why break out at all if Munsey knows the plan? Well, it’s indicative of noir: the outcome doesn’t matter as long as you’ve tried. The prisoners want to get out. All that matters is they try.

And try they do, but not before Warden Barnes resigns and places Munsey as the acting warden. His ascension to warden causes the inmates in the prison yard to riot and cause a distraction as Gallagher and his men throw Molotov cocktails at the guard tower.

The climax has officially begun. It’s just as brutal today as it was in 1947. Jules Dassin has wonderful shots and tight, fast-paced editing that makes for one of the best and most memorable climaxes of Hollywood’s Golden Age. If you’ve gotten this far, I assume (and hope) you’ve already seen it.

The guards in the tower fire their machine gun into the crowd of prisoners. It packs a punch today, and it was especially brutal in 1947 to see dozens of characters mowed down. Audiences had seen newsreels of battles during the war, but they rarely showed people getting shot and dying up close in front of the camera. While tame by today’s standards, it’s important to note that the filmmakers wouldn’t have gotten away with violence of this film had it not been for newsreels showing bombs, planes, and shooting during World War II.

The action in the climax is dynamic and dramatic. There’s great camera work as we zoom in on Joe and his men, who have tied Freshman Stack to a cart so he’ll be the first one to be shot, as they wheel him into the camera. From here on out, it’s fast-paced action all the way. Freshman Stack is lit up by the machine gun and Spencer, Kid Coy, and Soldier are killed within seconds of each other. Joe is the only one left and you think he has a chance until he’s shot in the back. He lives for a few more minutes, but we as the audience know it’s only a matter of time.

Gallagher’s impatience is the final nihilistic nail in the coffin. Joe’s missed his 12:15 window and still hasn’t gotten up to the tower to open the gate. Gallagher sums up his entire viewpoint of the entire film as the centrist character when he tells another inmate “The plan’s a flop. You’re on your own.” He tries to ram the gate with the truck they’ve brought into the prison yard, which is now in flames courtesy of Munsey’s marksmanship. The flaming truck is his pyre.

Joe finally makes it up the stairs, pulls the lever to the gate, and has a final fight with Munsey. The fight is quick and rather anti-climactic, although they each get some blows in and the captain hits Joe with an ammo belt (nice touch). But it’s not a surprise who wins, as Burt Lancaster is 8 inches taller and at least 50 pounds heavier than Hume Cronyn. We get a great shot of Lancaster's physical strength as he lifts Cronyn above his head and throws him to the mob below.

The final doom and gloom is when Joe sees the gate is blocked by Gallagher’s truck. It’s the ultimate condemnation of Gallagher’s every man for himself mentality. If he had waited a little longer, if he hadn’t been so quick to revert to his own needs and instead thought of the collective as a whole, then everyone in the prison would be free. Joe dies on the burning tower as the guards rush in and pelt the prisoners with tear gas.

We get one final scene that gives a lasting emotional punch. The camera pans past a completely empty cell R-17. All 6 men are dead. Calypso, who was injured in the breakout attempt, is patched up by Dr. Walters. The two deliver some great last lines:

Calypso [getting a wound sterilized]: Gee, that hurt, doc. That hurt plenty.

Dr. Walters: This place is full of pain, Calypso. You’re hurt, Collins—Collins and Munsey are dead. And the others. All those others. Why do they do it? They never get away with it. Alcatraz, Atlanta, Levenworth. It’s been tried a hundred ways from as many places. It always fails. But they keep trying. Why do they do it?

Calypso: I don’t know, doc. But whenever you got men in prison, they’re gonna want to get out.

Dr. Walters: But they learn. They must. Nobody escapes. Nobody ever really escapes.

It’s a bleak ending, possibly the most pessimistic in noir, which is really saying something. Calypso’s last line about men in prison wanting to get out implies the prisoners know they won’t succeed, but they have to at least try. It’s a small bit of optimism in a very nihilistic film. But it’s Dr. Walters’ last line that sticks with us most: Nobody ever really escapes. Even if you do your time and get out, your prison experience follows you for the rest of your life. Or you die trying to break out.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t end this with a bit of pessimism in keeping with noir’s philosophy. A few years after the film premiered, conservative groups and HUAC saw the film as leftist propaganda. It’s not hard to see why since the movie isn’t subtle about what it’s trying to say. Films like Brute Force put their creators under scrutiny. The film itself is not what caused Jules Dassin, Roman Bohnen, Art Smith, and Jeff Corey to be blacklisted, but it probably brought their previous activities under surveillance.

I mentioned Jules Dassin’s blacklisting at the beginning of this post, but it’s important to provide context for several of the actors who met the same fate.

Roman Bohnen, who plays the warden, was one of the heads of The Actors’ Laboratory Theatre, which was founded by a number of former Group Theatre actors. The Actors’ Laboratory was a politically active group. Those involved publicly spoke out against racial segregation and the theater accepted students and members of all races, which was still unusual at the time. The group was accused of communist leanings. Bohnen and other members were subpoenaed to appear before the California Senate, but they refused to answer any questions. Bohnen tried to keep The Actors’ Laboratory afloat even after the IRS revoked the theater’s tax-exempt status. He died of a heart attack during a performance in 1949. The Actors’ Laboratory disbanded a year later.

Art Smith was a member of the Actors’ Laboratory. Smith was blacklisted in 1952, which basically ended his film career, although he appeared on Broadway and later had some uncredited roles in movies.

Jeff Corey—who played “Freshman” Stack, the traitorous cellmate of R-17—helped Roman Bohnen and others establish the Actors’ Laboratory. He was called before HUAC in the early 1950s and refused to name names. Corey attended some CPUSA meetings with Jules Dassin but never officially joined, which makes his refusal to name names even more commendable. He mocked the HUAC panel and this, along with his refusal to name other Communists, caused him to be blacklisted for 12 years. During this time, he became a highly influential acting teacher. Luckily, he was able to work in films again starting in 1962 and continued working until the late 1990s.

The blacklisting of these figures came at a bleak time in the United States’ history, which is ironically fitting as it reinforces the nihilistic noir philosophy.